What is landscape? A perspective from Cairo

“A more functional perspective quickly demonstrates that humans not only…

Recently, the difference of concepts between “Fukei (scenery)” and “Keikan (landscape)” in Japanese was reported in the Journal of Landscape Research. This showed the different understanding among different cultural backgrounds and linguistic spheres. Western researchers have focused on the different appreciation of landscapes among different human races and climatic conditions. So I examined Japanese books to find the definition of landscape phenomena using the key words of “Fukei” and “Keikan”. And I categorized them in terms of the ability of human beings to find the landscape, the relationship between human beings and landscape objects, and the definition of landscape.

Gehring (2007) of the Swiss National Institute of Science interviewed 10 Japanese people about the difference in their understanding of “Fukei (scenery)” and “Keikan (landscape)” in Japan, and published the results in Landscape Research in the UK. The fact that such research was done by Western researchers and published in British journals shows that Western researchers have realized that the East has a concept of “landscape” that differs from that of the West. It was 45 years after Sullivan (1962) showed that Chinese culture was ahead to western countries in landscape appreciation.

The Japanese understanding of landscape was influenced by cultural influences such as Chinese landscape paintings and Western landscape paintings, so our understanding of landscape phenomena was influenced by both. In this study, in order to clarify the transition of Japanese people’s understanding of landscape, I investigated the definitions of landscape and scenery in Japanese books, and summarized the understanding of the phenomenon of landscape.

Kodera (1959) and other studies on landscape understandings from ancient times to the present can be seen. Some also partially describe landscape understanding in their books (Kuroda, 1937). However, none of recent publications reported on changes in the definition of landscape.

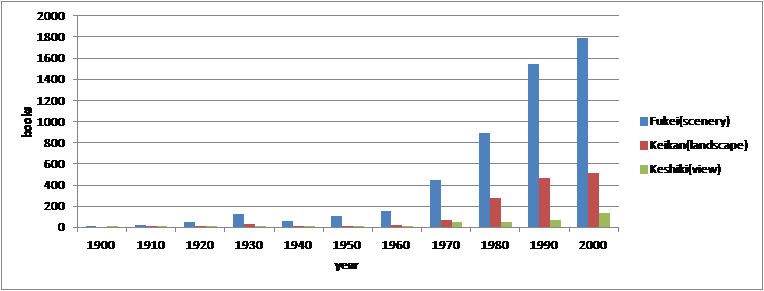

The National Diet Library has a large collection of various Japanese books. The number of books containing Fukei and landscape as keywords has increased rapidly since 1975 (Figure 1). This was partly due to the increase in printed matter, but also due to the landscape boom that began around the time of Higuchi’s (1975) “Structure of Landscape” (Aoki, 2001). This trend continues today and has become even more common in recent years due to the enactment of the 2005 Landscape Law.

A similar trend can be seen in the collections of the University of Tokyo and the University of Tsukuba libraries when looking at changes in academic books. I picked up books with clear descriptions of the definitions and characteristics of Fukei and landscape from the collections shared by both universities. By examining this, we can see how the landscape phenomenon was understood. Since the Fukei is a phenomenon that ordinary people know as a daily experience, these descriptions are considered to represent the general public’s understanding rather than specialists’ understanding.

2. Way of Analysis

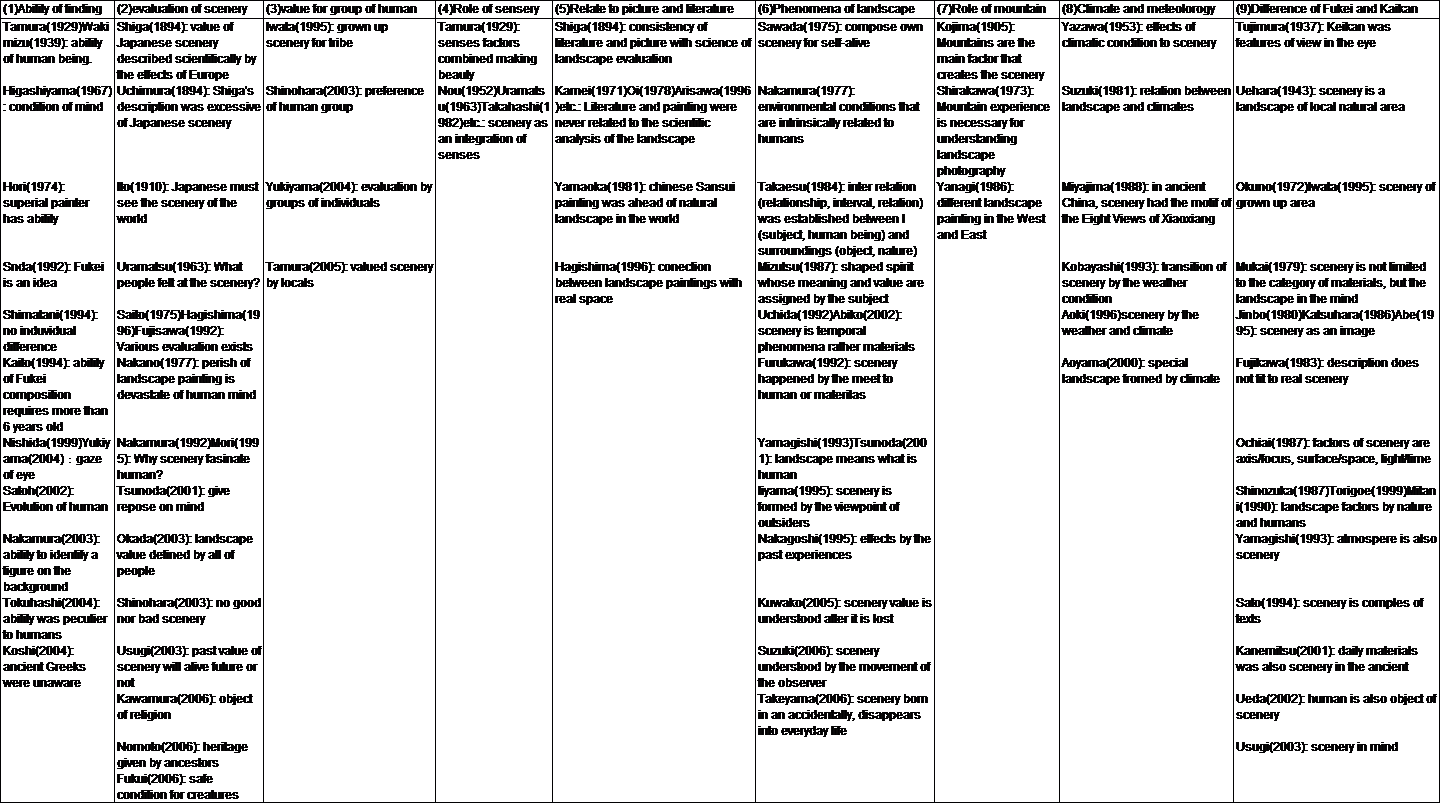

We examined books common to both universities, extracted sentences that clearly described the definition and characteristics of Fukei and landscape, and summarized them for each item. The items are summarized as follows: items related to humans who are the cause of the phenomenon of scenery, items representing the relationship between humans and visual objects that make up the scenery, and items related to visual objects.

Items related to humans are summarized as (1) ability to discover scenery, (2) value of scenery, and (3) value of scenery in a human group.

In the relationship between humans and visual objects, we summarize (4) the relation between the human receptors of the five senses and the landscape, (5) the expression of the landscape in the literature and paintings, and (6) the relationship between humans and the visual objects as a landscape phenomenon.

In terms of visual objects, (7) mountains in the landscapes, which were drawn as the center of landscapes in the beginning age, (8) the affect of climate and weather on landscape, and (9) the differences between Fukei and Keikan (landscapes), are summarized.

Tamura (1929) and Wakimizu (1939) wrote about human ability, stating that few people can find landscapes. Painter Higashiyama (1967) wrote that people’s mental states make them to see landscapes. Physicist Hori (1974) wrote that a good painter finds and paints them.

Senda (1992) wrote that landscapes are ideas because they are discovered by one’s own will. On the other hand, Shimatani (1994) pointed out the influence of culture and grown up scenery, but noted that there were no individual differences. Kaito (1994), a psychiatrist, stated that the concept of landscape is not understood by children, so he limits the application of the landscape composition method to people over the age of six. In particular, people can remember natural landscapes after ca. the age of 10 (Aoki, 2000), suggesting that landscapes should be complex perceptions.

Nishida (1999) and Yukiyama (2004) wrote that the landscape can be created by looking at it. Sato (2002) wrote that it was born through human biological evolution. This is consistent with Bourassa’s (1991) observation of brain evolution and the development of landscape comprehension. Nakamura (2003) pointed out that the ability to divide into figure and back ground shows landscape. Tokuhashi (2004) wrote that such abilities are unique to humans. Koshi (2004) noted that the ancient Greeks were unaware the landscape.

Shiga (1894) scientifically described the value of Japanese landscapes under the influence of Western culture. This description was accepted by many people. However, Uchimura (1894) pointed out that Shiga’s description overestimated the value of Japanese landscape because he saw outstanding landscapes of the United States, Europe, and continents which Japan did not have. Ito (1910) wrote that the Japanese should actually look at foreign landscapes and ensure the value of Japanese landscapes.

Photographer Uramatsu (1963) asked what people feel when they faced with landscapes. Saito (1975), Hagishima (1996), Fujisawa (1992) and others showed that there are various evaluations of desirable landscapes that differ from person to person. Nakano (1975) stated that if landscape paintings were to perish, it would be the devastation of the human heart. Nakamura (1992) and Mori (1995) questioned why the phenomenon of landscape fascinates people. The philosopher Tsunoda (2001) pointed out that it provides peace of mind.

Okada (2003) suggested that the value of landscape should be decided by all people there. Shinohara (2003) pointed out that there is no good scenery or bad scenery in a landscape, and that it is a matter of the mind of the people who are there. Usugi (2003) worried that past landscape evaluations will continue forever or not.

Kawamura (2006) wrote that landscapes become objects of worship. Nomoto (2006) pointed out that landscapes linked to religious beliefs are legacies left to us by our predecessors. In addition, Fukui (2006) stated the same as Appleton’s (1975) Prospect-Refuge theory that a landscape considered safe for animals is a good landscape.

Iwata (1995) pointed out the value of the grown up landscape for ethnic groups. Shinohara (2003) pointed out that there is a preference for landscapes as a group. Yukiyama (2004) also pointed out the value by the group to which the individual belongs. Tamura (2005) pointed out that there are special landscapes for local people. Such differences between groups have been noticed since the 1970s in the United States, a multi-ethnic country, and many experiments have been repeated (Aoki, 1999).

Tamura (1929) described the landscapes formed by “combining sensory stimulus to create beauty”. Geographer Noh (1952), landscape photographer Uramatsu (1963), and landscape architect Takahashi (1982) have explained the phenomenon of landscape as an integration of these senses.

On the other hand, there are also works that describe the relationship between individual sensations and landscapes. Hidaka (1989) focused on soundscapes.

Shiga (1894) advocated an epoch-making proposal that matching of literature and paintings with science in the landscape evaluation which is still relevant today. After his description, many people such as Kamei (1971), Oi (1978), and Arisawa (1996) have pointed out that literature and painting have never actually been linked to the scientific analysis of landscapes.

Yamaoka (1981) pointed out that Sansui paintings in old China appreciated natural scenery that are ahead in the world.

On the other hand, Hagishima (1996) studied the relation between landscape paintings and real spaces which was an epoch-making attempt.

Haga (2004) points out that Sansui painting is not just a representation of the landforms, but a representation of the scenery in mind.

Japanese word Fukei, like scenery, is also due to the physical conditions that exist on the surface of the earth. In the Western countries, people tried to describe physical phenomena that do not change much over time to represent landscapes (Landschaft, Paysage, etc.). From the Japanese perspective, this was a new concept and seemed scientific. However, there was a sense of incongruity in the Japanese expression of scenery, i.e.Fukei. This is also the reason why the new coined Japanese word Keikan “landscape” was established.

Sawada (1975) pointed out that landscape is a phenomenon that he has formed in order to live. Nakamura (1977) considered that landscape is an environmental condition that is intrinsically related to humans. Takaesu (1984), a psychiatrist, defined Fukei as the ‘inter relation (relationship, interval, relation)’ that has been established between ‘I (subject, human being)’ and ‘surroundings (object, nature)’. Mizutsu (1987), citing Schwindt’s theory, expressed that the landscape itself is a “spirit with form” to which meaning and value are given by the subject, human. Furukawa (1992) wrote that Fukei is a phenomenon that occurs when people meet people and things. Uchida (1992) and Abiko (2002) pointed out that the Fukei is not so much an object itself as a phenomenon that occurs at a certain time.

Yamagishi (1993) and Tsunoda (2001) realized that thinking about the Fukei is the same question as discussing what it means to be human. Iiyama (1995) argued that “Fukei” is formed by the perspective of an outsider, that is, by an outsider’s point of view. Nakagoshi (1995) described the influence of past experiences on landscape.

Kuwako (2005) described a Fukei whose value cannot be recognized until it is lost. Also, Suzuki (2006) pointed out that there is a Fukei that can be understood by the movement of the observer. Takeyama (2006) points out that Fukei is born in a random moment and disappear after becoming routine. Noro (1999) points out that the Fukei may or may not be visible depending on the time.

Kojima (1905) compared Sansui landscape paintings that had been handed down in Japan since ancient times, and noted that mountains are the main factor in creating Fukei. This was something that Japanese people who were familiar with Sansui landscape paintings could easily understand. He also led to research in which people considered the relation between mountains and landscapes (Shiota, 1981).

Shirakawa (1973), a mountain photographer, stated that experience in mountains is necessary for understanding of landscape photography. In this way, mountain scenery taught us that on-site experience is important for understanding landscapes. Ponting (1910), a landscape photographer who came to Japan in the Meiji era, had a good understanding of mountain scenery. At Mt. Myojin between Lakes Shoji and Lake Motosu, he experienced what it would be like to see the Matterhorn from Gornagrad in Switzerland. The view of Mt. Fuji from Lake Motosuko, where he liked to stay, became the picture of banknotes that were used until recently.

Dutch landscape paintings, which had given an impact on the world, depicted the mountains of the Alps in the flat landscape of the plains near the Netherlands. From this, we can understand that mountains are an important landscape element. However, if you look at the landscape paintings of England, where there are no mountains, you can find that there are no mountains. Yanagi (1986) pointed out this as the difference between Western and Eastern landscape paintings.

Yazawa (1953) investigated the effects of climatic conditions on landscapes and described them as characteristics of landscapes interwoven with nature and culture. This idea was also nurtured in landscape architecture, and Suzuki (1981) explained the relationship between climate and landscape from his own experience.

On the other hand, changes in landscape caused by weather conditions became the subject of research by Kobayashi (1993). Such themes were the motifs of many landscapes such as the Eight Views of Xiaoxiang in ancient China in the 10th century (Miyajima, 1988). Currently, it is being studied as an ephemeral landscape in western countries (Nohl, 1997). People who have seen Turner’s paintings can easily understand that there were people in western countries who enjoyed such landscapes.

Aoki (1996) wrote that climate and weather form Fukei. Aoyama (2000) investigated and summarized the special landscapes created by the climate.

There is a Japanese word Fukei that is similar to landscape. According to Tsujimura (1937), landscape is the characteristic of the scenery reflected on the eye. It is said that forestry scholar Dr. Manabu Miyoshi coined the Japanese word Keikan when translating the German Landschaft into Japanese. I can’t believe that the doctor didn’t know the Japanese words “Fukei, scenery” and “Keshiki, view”, so he thought that Landschaft is understood as a different concept of them. Ide (1975) also pointed out that it would have been better to translate it as an area of scenery. Uehara (1943) described Fukei as a scenery in a local natural area. This concept is still used in geography today.

Since Tsujimura, the concept of landscape, which established in the Western culture, became as a term for measuring and describing the physical conditions of a region in Japan. But landscape came to be understood as a receiving phenomenon, including psychological phenomena in Japan. Okuno (1972) and Iwata (1995) used the term ‘grown up Fukei’ to introduce what lies deep in people’s minds as scenery. Architect Mukai (1979) did not limit the term “Fukei” to the category of mere objects, but used it in a fairly broad sense, including the scenery of the mind. Jimbo (1980), Katsuhara (1986), Abe (1995) and many others have captured Fukei as images. Fujikawa (1983) described in “The Poetry of Scenery” that the actual Fukei and what is described did not match. Shinji (1999) stated that “Fukei” is a literary example and “landscape” is a scientific example.

Ochiai (1987) cites axis/focus, surface/space, light/time, etc. as elements of landscape. This is a landscape analysis method as an image that was started by Shafer (1969). Many researchers followed this trend and proceeded with their researches by considering photographs, slides, and computer images as landscapes. This represented the flow of Western landscape research, and was a very natural “landscape” research. However, for Japanese, there were some people who wondered it. Kushida (1980), in an article introducing Cornish landscape research, questioned why only people in the natural sciences were pursuing landscape research.

Shinozuka (1987), Torigoe (1999), and Mitani (1990) considered the landscape to include both nature and human activities. Yamagishi (1993) argued that atmosphere is also Fukei. Sato (1994) described Fukei as an accumulation of texts. Kanemitsu (2001) examined life in ancient times and argued that in ancient times everyday objects should be included in the Fukei. Zen scholar Ueda (2002) also considered people as Fukei elements. Usugi (2003) described this as an imaginary Fukei.

From the results above, two issues can be concluded about the understanding of landscape phenomena.

In the future, the advanced researches will be needed on landscape experiences, landscape paintings, and landscape descriptions, and also advanced processing research on response of the brain and research on measurable conditions that produce emotions.

I would like to thank Professor Jay Appleton for showing the importance of landscape experience research in the UK. I would like to express my gratitude to Professor Hajime Nakamura, who gave me his opinion at the time of the presentation at the Japanese Institute of Landscape Architecture. I am grateful to Professors Yoshio Nakamura, Tadahiko Higuchi, and Osamu Shinohara for inviting me to study landscapes during my university days. The reviewers gave me good ideas on how to summarize.

Abe, H.(1995)Nihon kukan no tanjo; Birth of Japanese space, Serika Books, Tokyo, 17p.

Abiko, K.(2002)Fukei no tetshugaku; Philosophy of scenery, Nakanishiya Publication,Kyoto,256pp.

Aoki, S.(1996)Shizen wo utsusu; Photography of nature,Iwanami,Tokyo,3p.

Aoki, Y.(1999)Review Articles: trends in the studies of the psychological evaluation of landscape, Landscape Research 24(1), 85-94.

Aoki, Y.(2000)Evolution of Landscape Appreciation in the History of Landscape Painting and in the First Remember of Landscape.Japanese Institute of Landscape Architecture63(5), 371-374.

Aoki, Y.(2001)Trends of Understanding of Landscape Appreciation in the Books Published since Meiji Era, Japanese Institute of Landscape Architecture64(5),469-474.

Aoyama, T.(2000)Nihonon no kikou keikan; Climatic landscape in Japan, Kokonshoin, Tokyo, 181pp.

Appleton, J.(1975)The Experience of landscape, John Wiley & Sons, London, 293pp.

Arisawa, M.(1996)Chi no Fukei; Scenery of intelligence, Nikkagiren Press, Tokyo, 207p.

Bourassa, S.C.(1991)The Aethetics of Landscape.Belhaven Press, London, 168pp.

Fujisawa, N.(1992)Jissen keikanron; Practical theory of landscape, Chikyusha, Tokyo, 3p.

Fujigawa, Y.(1983)Fukei no Shigaku; Poetry of Scenery, Hakusuisha,Tokyo, 347p.

Fukui, Y.(2006)Shakai Kiban Shisetsu no tameno Keikan Sekkeigaku; Landscape design for infrastructure facilities, Corona press, Tokyo, 228pp.

Furukawa, A.(1992)Kankyo Imeijiron: Theory of Environmental Image,Kobundo, Tokyo, 5p.

Gehring, K. and Kohsaka, R. (2007)‘Landscape’ in the Japanese Language: Conceptual Differences and Implications for Landscape Research.Landscape Research 32(2), 273-283. Haga, T.(2004)Nihonjin no Fukeihyougen; Japanese landscape expression, Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo, 84pp.

Hagishima, S.(1996)Fukeiga to Toshikeikan; landscape painting and cityscape, Rikotosho, Tokyo, 1p.

Higuchi, T.(1975)Keikan no Kozo; The visual and spatial structure of landscapes, Gihodo, Tokyo, 168pp.

Hidaka, T.(1989)Furansu Oto no Fukei; Scenery of sound in France, Roko Press, Tokyo, 308p.

Higashiyama, K.(1967)Fukei tono Taiwa, Shinchosha, Tokyo, 51p.

Hori, J.(1974)Butsuri no Fukei, Kodansha, Tokyo, 214p.

Ide, H.(1975)Keikan no Gainen to Keikaku; landscape concept and planning.City Planning Review83, 10-13.

Iiyama, M.(1995)Fukei toshiteno Joho Shakai; Information society as a scenery, Sekaishoin, Tokyo, 165p.

Ito, G.(1910)Nihon Fukei Shiron; Japanese Landscape New Theory,Maekawabuneikaku, Tokyo, 373pp.

Iwata, K.(1995)Fukeigaku to Jibungaku; Scenery and self study, Kodansha, Tokyo, 75p.

Jinbo, T.(1980)Fukei kara Fukeibi he; From scenery to scenic beauty, Geijutsu to Youshiki:Bijutu Press, Tokyo, 155-176.

Kaito, A.(1994)Fukei Kouseiho-sono Kiso to Jissen; Landscape Composition Method – Its Fundamentals and Practice, Seishinshobo, Tokyo, 13p.

Kanemitsu. J.(2001)Gensho no Fukei to Sinboru; Primordial landscapes and symbols, Daishuukan Books, Tokyo, 324pp.

Katsuhara, F.(1986)Mura no Bigaku; village aesthetics, Ronsosha, Tokyo, 24p.

Kamei, K.(1971)Tabi no Techo kara; From a travel notebook. The Complete Works of Katsuichiro Kamei13, Kodansha, Tokyo, 495-496.

Kawamura, T.(2006)Kowareiku Keikan; Crumbling landscape.Keiogijukudaigaku Press, Tokyo, 298pp.

Kobayashi, T.(1993)Utsuroi on Fukeiron; Theory of landscape changing, Kashima Press, Tokyo, 12-15.

Kojima, U.(1905)Nihon Sansuiron; Theory of Japanese landscape, Ryubunkan, Tokyo, 460pp.

Koshi, K.(2004)Fukeiga no Shutsugen; Appearance of landscape painting, Iwanamishoten, Tokyo.179pp.

Kodera S.(1959)Fukeikan no Seichohatten – Tokuni Kinsei kara Kindai/Genda heno Tenkan; The Growth and Development of Landscape Views -Especially the Transition from the Early Modern to the Modern and Now-, Chiri4(8), 948-958.

Kuroda, H.(1937)Nihon Fukei Dokuhon; Reading book of Japanese scenery, Kokonshoin, Tokyo, 257pp.

Kushida, M.(1980)Kaisetsu Fukei nituite, Fukeino Mikata; Commentary about scenery, view of scenery, Chuokoronsha, Tokyo, 157-178.

Kuwako, T.(2005)Fukei no nakano Kankyo Tetsugaku; Environmental Philosophy in Scenery, Tokyodaigaku Press, Tokyo, 251pp.

Mizutsu, I.(1987)Keikan no Shinso; depth of landscape, Chijinshobo,Kyoto, 30-31.

Mitani, T.(1990)Fukei wo Yomu Tabi; Travel of reading scenery, Maruzen, Tokyo, 4p.

Miyajima, S.(1988)Ohmi Hakkei no Seiritsu, Ohmi Hakkei; Establishment of Ohmi 8 views, Ohmi 8 views, Shiga Prefectural Museum of Modern Art, 8-11.

Mori, H.(1995)Fukei no Shujigaku; landscape rhetoric, Eihousha,Tokyo, 439p.

Mukai, M.(1979)Nihon kenchiku, Fukeiron; Jaoanese Architecture,Theory of Scenery, Sagamishobo, Tokyo, 17p.

Nakagoshi, N.(1995)Keikan no Grand Design; Grand Design of landscape, Kyouritsu Press, Tokyo, 178pp.

Nakamura, S.(1992)Alupusu ha Naze Utshukusiika; why the alps are beautiful, Shubunsha, Tokyo, 5p.

Nakamura, Y.(1977)Keikan Genron; Original landscape theory, Civil Engineering System 13 Landscape Theory, Shokokusha. Tokyo, 1-31.

Nakamura, Y.(2003)Kanokyo ha Donyounisite Keikan ni Naruka; how the environment becomes a landscape, environmental hermeneutics, Gakugei Press, Kyoto, 103p.

Nakano, J.(1975)Fukei wo Egaku; paint a landscape, Bijutsu Press, Tokyo, 6p.

Nishida, M.(1999)Setonaikai no Hakken; Discovery of the Seto Inland Sea, Chokoron Shinsha, Tokyo, 263pp.

Nohl, Werner(1997)Die ephemere Landschaft, Materialiensammlung des Lehrstuhl.fuer Bodenordunung und Landentwicklung der Technishen Universitaet Muenchen, Heft 18, 115-122.

Nomoto, K.(2006)Kami to Shizen no Keikanron; Landscape Theory of God and Nature, Kodansha, Tokyo, 289pp.

Noro, K.(1999)Moji no Fukei; landscape of characters, Seiseisha, Kyoto, 174pp.

Noto, T.(1952)Shuraku no Chiri; Geography of settlements, Kokonshoin, Tokyo, 15p.

Okada, M.(2003)Tekunosuke-pu; Tecnoscape, Kashima Press, Tokyo,188pp.

Ochiai, T.(1987)Fukei no Kousei to Enshutsu; Composition and production of scenery, Shokokusha, Tokyo, 7p.

Okuno, T.(1972)Bungaku ni okeru Genfukei; original landscape in literature, Shueisha, Tokyo, 11p.

Ohi, M.(1978)Fukei no Banka; elegy of scenery, Anvielle, Tokyo, 321pp.

Ponting, H.G. (1910):In Loutus-Land Japan. Macmillan and Co., Ltd., London, 381-395.

Saito, S.(1975)Nihonjin to Shokubutu/ Dobutsu; Japanese people and plants/animals, Yukihanasha, Tokyo, 13-14. Sato, K.(1994)Fukei no Seisan/Fukei no Kaiho; Scenery

Production/Opening Scenery, Kodansha, Tokyo, 5p.

Sato, F.(2002)Hikari to Fukei no Butsuri; Physics of Light and Scenery, Iwanami, Tokyo, 96pp.

Sawada, M.(1975)Ninshiki no Fukei; scenery of recognition, Iwanami, Tokyo, 47p.

Senda, M.(1992)Fukei no Kozu; scenery composition, Chijinshobo,Tokyo, 3-4p.

Shafer, E.L.Jr., Hamilton, J.F.Jr. and Schmidt, E.A. (1969) Natural landscape preferences: a predictive model.J. of Leisure Research, 1(1), 1-19.

Shiga, S.(1894)Nihon Fukeiron; Theory of Japanese Scenery, Seikyosha, Tokyo, 219pp,

Shimatani, Y.(1994)Kasen Fukei Dezain; river scenery design, Sankaido, Tokyo, 3p.

Shita, S.(1981)Yama to Fukei; Scenery and Mountain, Tokyo University Open Course 32 Mountain, Tokyodaigaku Press, Tokyo, 101-126.

Shinji, I.(1999)Fukei Dezain; Scenery Design, Gakugei Press, Kyoto,10-11.

Shinozuka, A.(1987)Toshi no Fukei; Scenery of City, Sanseido, Tokyo, 206pp.

Shinohara, O.(2003)Doboku Dezainron; Design theory of civil engineering, Tokyodaigaku Press, Tokyo, 331pp.

Shirakawa Y.(1973)Sangaku Shashin on Giho; techniques of mountain photography, Rikogakusha, Tokyo, 85pp.

Sullivan, M. (1962) Birth of landscape painting in China, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angels, 213pp.

Suzuki, M.(2006)Fukei no Karyudo; landscape hunter, Shokokusha, Tokyo, 223pp.

Suzuki, M.(1981)Toshi to Midori to Keikan Kousei; City, greenery and landscape composition, Maki Press, Tokyo, 213pp.

Takaesu, Y.(1984)Nakai Hisao Chosakushu Bekkan Fukei Kouseiho; Hisao Nakai’s work collection separate volume landscape composition method, Iwasakigakujutu Press, Tokyo, 124p.

Takahasi, S.(1982)Fukeibi no Souzo to Hogo; Creation and protection of scenery beauty, Dimyosha, Tokyo, 1-2.

Takeuchi, T.(1989)Subarashii Shizen wo Utsusu; photograph beautiful nature, Asahishinbunsha, Tokyo, 120pp.

Takeyama, N.(2006)Fukei, Toshi Keikan Sutadei; Scenery, Feature Urban Landscape Study, INAX Press, Tokyo, 150-151.

Tamura, A.(2005)Machidukuri to Keikan; Town planning and landscape, Iwanami, Tokyo, 231pp.

Tamura, T.(1929)Shinrin Fukei Keikaku; forest landscape planning, Seibido, Tokyo, 230pp.

Tokuhashi, Y.(2004)Kankyo to Keikan no Shakaishi; Social history of environment and landscape, Bunkashobohakubunsha, Tokyo, 237pp. Torigoe, H.(1999)Keikan no Souzou; creation of landscape, Showado, Kyoto, 10-11.

Tsujimura, T.(1937)Keikan Chirigaku Kouwa, Chijinshokan, Tokyo, 362pp.

Tsunoda, Y.(2001)Keikan Tetsugaku heno Ayumi; Steps toward Landscape Philosophy, Bunkashobohakubunsha, Tokyo, 337pp.

Ueda, S.(2002)Zen no Fukei; scenery of Zen, Ueda Kanshoshu 5,Iwanami,Tokyo, 360pp.

Uchida, Y.(1992)Fukei toha Nanika; what is a scenery, Asahishinbunsha, Tokyo, 56p.

Uchimura, K.(1894)Shiga Shigetaka Cho “Nihon Fukeiron”; Shiga Shiga, “Theory of the Japanese Scenery”, Rokugozasshi 168, 29-31.

Uehara, K.(1943)Nihon Fukei Biron; Japanese Scenery Aesthetics, Dainihon Press, Tokyo, 39p.

Usugi, K.(2003)Nihon no Kukan Ninshiki to Keikan Kousei; Spatial Recognition and Landscape Composition in Japan, Kokonshoin, Tokyo, 511pp.

Uramatsu, S.(1963)Fukei Shasin; scenery photography, Asahishinbunsha, Tokyo, 6p.

Wakimizu, T.(1939)Nihon Fukei Shi; scenery magazine of japan, Kawadeshobo, Tokyo, 1-2.

Watsuji, T.(1935)Fudo, Ningengakuteki Kousatsu; climate, anthropological considerations, Iwanami, Tokyo, 407pp.

Yamaoka, T.(1981)Chugoku oyobi Nihon no Sansuiga no Tokushitu nituite, Fukeiga Seiritsu no Imi; the characteristics of landscape paintings in China and Japan, Meaning of landscape painting,Showa55nendo monbusho kagakukenkyuhi seika houkokusho; 1980 Ministry of Education Scientific Research Fund Results Report, 13-20.

Yamagishi, T.(1993)Fukei toha Nanika; what is scenery, Nihon Hososhupankyoukai, Tokyo, 8p.

Yanagi, S.(1986)Shizen kei – Hidashi to Nishi, touzai no Fukeiga; Natural Scenery-East and West, East-West Landscape Painting, Shizuoka Kenritsu Bijutsukan, Shizuoka, 12-17.

Yazawa, D.(1953)Kikou Keikan; :climate landscape, Kokonshoin, Tokyo, 227pp.

Yukiyama, G.(2004)Jo, Shitsurakuen; Introduction, Paradise Lost, Yokohama Bijutsukan, Daishukan Press, Tokyo, 1-2.