Supporting Urban Poor Women’s Leadership to Respond to Lake and Wetland’s In-filling Practices and Urban Dispossession in Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Johanna Brugman, Leakhana Kol and Mark Kelton

Research Background

Cambodia, a country with a ‘disjointed’ form of governance in which state-private alliances bypass urban legislation and consequently struggles in governing its resources in an equitable way. Since 2003, over 60% of Phnom Penh’s lakes and more than 40% of wetlands have been in-filled by developers, leading to flooding, pollution, and loss of fishing breeding grounds. Also, forced evictions of urban poor families have occurred leading to a loss of livelihoods, connections to place, and rights to land and water1.

Urban poor communities, many led by women, have organized to respond to the increasing threats of dispossession caused by in-filling practices. These citizenship practices are not fully documented and face a risk of not being properly supported by civil society organizations and funding agencies. On the one hand studies indicate that secure rights to land and other property can protect women from experiencing domestic violence by strengthening their position within their families or by providing women with a stronger ability to exit abusive relationships2; however, when women are in leadership positions at the forefront of the struggle of land rights power dynamics within their families, communities and their cities can also threaten their security and well-being3.

Using a gender lens, this research aims to produce context-specific knowledge on the experiences of urban poor women to lake and wetlands’ in-filling practices in Phnom Penh and use this knowledge to inform how support is given to women to lead community-based responses to this form of dispossession.

Research Objectives

- Understand the structural dynamics of lake and wetlands in-filling practices in Phnom Penh

- Understand the cultural, emotional, and socio-economic connections of women from urban poor communities to lakes and wetlands in Phnom Penh

- Understand women’s responses to lakes and wetlands in-filling practices

- Understanding the challenges and support given to women in leadership roles in urban poor communities facing lake and wetlands in-filling

Methodology

The research used a variety of qualitative research methods to gather data based on the research objectives. Document reviews have been conducted to understand the dynamics of lake and wetlands infilling practices in Phnom Penh, as well as review existing research to inform our work. Focus group discussions and life stories were collected to understand the experiences of urban poor residents, in particular women, from two subject sites: Tompoun/Cheung Ek Wetlands and Boung Tamok Lake in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Also, interviews were undertaken with key informants from three NGO’s: Urban Poor Development Women, Equitable Cambodia and Sahmakum Teang Tnaut.

Field visits were divided in 2 phases. The first phase included an initial visit to the sites to scope the research sites and establish relationships with the communities. A second visit was done in the second phase to collect data. A total of 3 focus group discussions with women and men from three different communities (2 communities in Tompoun/Cheung Ek Wetlands and 1 community in Boung Tamok Lake) were conducted. Furthermore, 13 individual life stories from urban poor women from the three different communities were collected. Also, 1 interview was undertaken with key informants from the NGO Urban Poor Development Women. The name of the communities from which participants participated in our research included:

Tompoun/Cheung Ek Wetlands

o Prek Takong 1 (PTK1), Sangkat Chak Angre Loeu, Khan Meanchey

o Prek Takong 2 (PTK2), Sangkat Chak Angre Loeu, Khan Meanchey

Boung Tamok Lake

o Samrong Tbong (SRT) Community, Sangkat Samrong, Khan Prek Phnov

Both the FGD and individual stories helped us to understand both the broader context and history of each community, including the relationships and significance of wetlands for urban poor residents, as well as the specific experiences of women caused by the infilling practices of these ecosystems, as well as their leadership roles. Members from our team in Australia conducted the document reviews. Members from our research team in Cambodia conducted the FGDs and life stories in Khmer and translated these into English. Researchers used a questionnaire developed by the research team as a guide to the FGDs and life stories, which was also used to take notes of both. Photographs were also taken from both subject sites and some of the participants of the research.

The research was conducted taking into account the following considerations to ensure ethical behaviour and safeguard the interests of the participants:

- Before participation all participants received verbal information on the details of the project, including main objectives, purpose, details of how the information will be used and measures to ensure participant’s confidentiality. This information was also given to our partner the NGO Urban Poor Women Development (UPDW) in Phnom Penh.

- Before participation all participants received verbal information on the details of the project, including main objectives, purpose, details of how the information will be used and measures to ensure participant’s confidentiality. This information was also given to our partner the NGO Urban Poor Women Development (UPDW) in Phnom Penh.

- Before conducting any interview or collection of stories an informal conversation with the participant was undertaken to explain the details of the research and ethical measures taken and ask them whether they want to participate in the research. Verbal informed consent was asked from every participant before collecting information from them.

- Participants were allowed to freely decide to participate or not in the research and withdraw at any time.

- Confidentiality of the participant was safeguarded by removing names and personal details from the data once it is collected and used in research reports and publications. Only the research team had access and knowledge of the participants of the study.

- All data was stored securely in our personal computers with access only by the research team.

- Contact details of the research team in Cambodia was shared with participants in case they had any questions or concerns in the future regarding the study.

Once data was collected, the research team organized the information collected according to the objectives of the research. A research report was produced with a summary of the main findings from the focus groups discussions. The life stories of women were also annotated and included direct ‘phrases’ from the participants.

Story-map

Using the software MapBox https://www.mapbox.com/ our team have started creating a story map based on our research in Phnom Penh. The story map displays the narratives of our research spatially and will serve as a dynamic tool to share the results of our research with wider audiences.

Covid-19

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, some members of the research team where unable to travel to Phnom Penh. Despite this, the team worked together in developing the research objectives, guiding questions, and analysing the information collected. Online platforms such as zoom and google files were used to have meetings and regularly share information.

Research Results

Field Site 1: Boung Tamok Lake

Boeung Tamok is the largest remaining lake by surface in Phnom Penh with an area of approximately 3,200 hectares. The lake is located in the north-western part of Phnom Penh and expands across six Sangkats or districts of the city. Historically Boeung Tamok has been an important source of livelihood for farmers and a natural reservoir for the city of Phnom Penh.

In 2020 approximately 300 urban poor families, or 1000 people, lived along the borders or within the lake4. Most of their houses are small and poorly constructed and are in the middle of the lake, or next to a highway to the west of the lake. Many of these families depend on the lake and its resources for their livelihood. Due to its large size the lake offers a range of fishing opportunities such as fish farming, fish trapping and fishing with nets. Also, there are forage-able plants and animals that grow or live in the lake’s shore such as morning glory, lotus flower seed pods, lotus stems, snails and frogs. Consequently, urban poor families rely on the lake for food security and income.

In February 2016 the Royal Government of Cambodia released a sub-decree to declare the lake as state public land. The demarcation established the boundary of the lake for the first time without consultation with stakeholders nor consideration of the rights of the people that use the lake on a daily basis. Approximately 300 families’ homes were affected by the sub-decree. The residents were concerned that despite the lake being declared as state public land, the RGC could decide to use the land for economic purposes which could lead to evictions and other negative consequences.

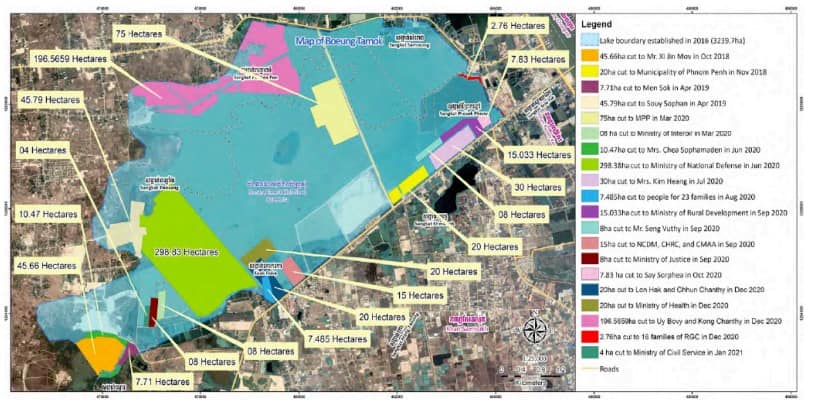

In fact, the declaration has enabled the transformation of the lake by facilitating in-filling practices for the development of infrastructure. In 2016 a road was built across the lake to create connectivity of the city to the National Highway 151. Since then various sub-decrees have been passed by the government to allocate sections of the lake for development of government facilities including government buildings, carparks and hospitals. Furthermore, additional sections of the lake have been given to government officials, their families, and foreign investors without transparency on the future use of the land. Some sections of the lake have been given to families living near the lake; however urban poor families have been excluded from this. The map below produced by Sahmakum Teang Tnau (STT) in 2021 shows the land reclamations affecting Boung Tamok Lake.

Since 2019 urban poor families living along and within the lake have been evicted or received threats of eviction due to occupying ‘state public land’. A research study conducted by STT in 20195 on Boeung Tamok found that 71 families were facing eviction, 15-25 were at high risk of eviction, and at least 204 families were at risk of being evicted in the future. Some of the devastating consequences of such evictions could be loss of housing and income, disrupted education for children, violence, and debt. For example, the research explained that many families had borrowed money from MFIs or informal money lenders to buy fishing resources. If the equipment is destroyed by authorities during evictions, this debt will increase. Several families have been handed eviction notices in 2020, despite the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic.

In environmental terms, Boeung Tamok continues to serve as a flood protector against northern-based water flows to Phnom Penh city. The dike which runs east to west along the southern shore of the lake effectively prevents northern-based floodwaters from entering the inner city and inundating large swaths of Phnom Penh. As the lake is infilled for development purposes, without proper environmental impact assessments millions of people in Phnom Penh and surrounding areas could be negatively impacted by flooding events.

Samrong Tbong (SRT) Community, Sangkat Samrong, Khan Prek Phnov

Samrong Tbong (SRT) Community has approximately 200 families or 98 dwellings. In 1989, people started to settle down in Samrong Tbong (SRT) village, for fishing, aquaculture/pisciculture, growing morning glory, farm lotus roots, doing seasonal rice farming, as well as planting corn and cucumber (in dry season). Most families come from rural Cambodian provinces and belong to Khmer ethnic, Vietnamese and Khmer-Muslim backgrounds. Also, there are Chinese people doing big scale fish farming in the area. In 1995, families in SRT village claimed land title from the district government but were unable to obtained it. So far, only some families have a family book and ID card (ID documents). Residents of SRT community claim these were given to most adults in the community by local authorities so that they could vote during national elections.

From 2016, people could not practice their annual seasonal rice farming since the lake was declared a natural reservoir of water from the city of Phnom Penh. This was at the time where the boundary of the lake was demarcated by the government and the lake was declared public state land. Between 2016-2019 people continue to do small-scale fishing, aquaculture/pisciculture, and farm morning glory and lotus flower. In 2019, local authorities stopped allowing people to set up their fish farming equipment on the lake and suspend their livelihood activities. Local authorities requested people

to suspend these because the government released a series of sub-degrees to fill-in or reclaimed some parts of the lake to construct a market, parking lot, government buildings, and other private and business activities.

At the time of this research most people still relied on the lake resources for their livelihoods. Also, residents have established home-based businesses which they rely on to earn income and sustain their families. Some young women, for example, run small business in front of their home such as sewing and small shops. On average, people in this community have an income of USD $5-8 per day. Most residents have debts. They have borrowed money from private money leaders and microfinance institutions at high interest rates.

Residents of this community are organized. They have received support and capacity building programs by local NGOs on mapping, social media advocacy, how to write letters to governments and environment issues. They are a progressive community that want to collaborate with local authorities; they do not advocate against the government. People in this community are worried about the in-filling of the lake and afraid that eviction might happen soon. They have had meetings with local authorities (Sangkat/District and Khan/Village) to request land title registration and to preserve

the natural estate of the lake for keeping their livelihoods as well as its role of being a natural water reservoir of Phnom Penh. No action has occurred because of these meetings. Community residents plan to organise a meeting with Phnom Penh City Hall to claim land title. They think that if they obtain land title registration, they will protect the lake and their livelihoods.

Field site 2: Tompoun/Cheung Ek Wetlands

The Tompoun/Cheung Ek wetlands are located at the south of Phnom Penh and include lakes, lagoons, marshes, rivers, streams and flooded fields comprising about 1,500 hectares. They kay lake in the area is known by locals as Boeung Tumpun. The wetlands receive almost 70% of Phnom Penh’s rain and wastewater. The variety of aquatic plants found in the wetlands such as morning glory Ipomoea aquatica, water celery Oenanthe javanica, and water mimosa Neptunia oleracea assist in slowing the flow of the water and purifying it naturally. Thanks to the wetlands, Phnom Penh is protected from floods. Local communities have been living in the area since the 1970s. The wetlands are used for a variety of purposes by the people including planting aquatic crops on the surface of the lake, fishing, raising ducks and farming. It is estimated that more than 1000 vulnerable poor families depend on the wetlands to sustain their livelihoods (LICADHO, CYN, EC, STT, 2020)6. Many communities live on the shores of the lakes, others live on the exit rivers or inside the wetlands in houses on stilts. Fish, birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians and insects are also an important part of the wetlands.

ING Holdings Co has been developing a satellite city covering 2,572 hectares of the Tompoun/Cheung Ek Wetlands since 2004. The land for the project has been given to the company by the government, and land has been sub-divided and leased to investment partners. It is expected that as part of the project an international school, retirement villages for Chinese families, and a hospital and housing for Japanese elderly people will be developed. Furthermore, the project proposes the development of government buildings, factory outlets, and shopping centres. These plans target foreigners such as from China and Japan rather than local Khmer people. The following Table provides a summary of the companies involved in development projects on the wetlands.

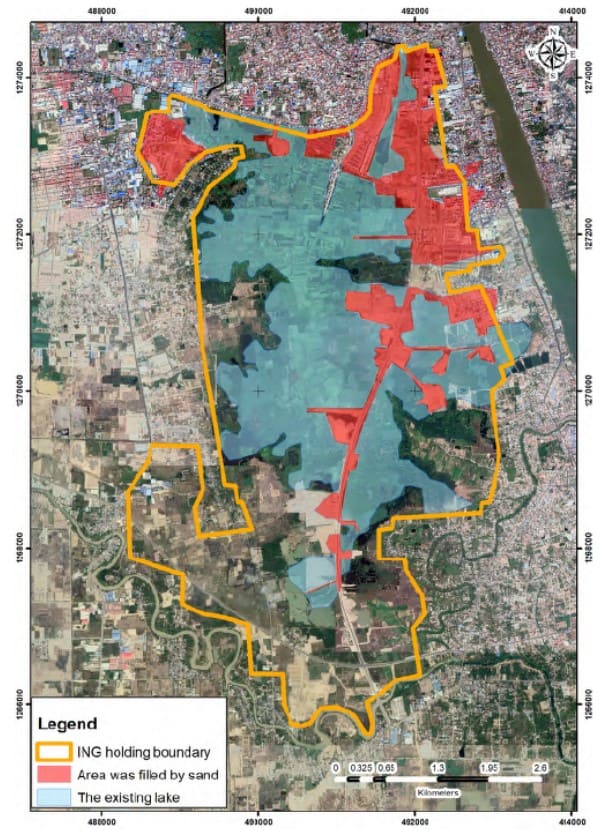

The project has the full support from the state and is thought to be in line with the 2035 Phnom Penh master plan. In the last two years more than 70% of the wetlands have been leased to private companies or individuals and parts have been filled-in as seen in the following map. The wetlands are now likely to be destroyed entirely with over 95% of the 1,500 hectares already leased to developers. This happened even when legally only a 520-hectare lake making part of this ecosystem was demarcated as public state land, rather than the whole 1,500-hectare wetlands7.

Prek Takong 1 (PTK1), Sangkat Chak Angre Loeu, Khan Meanchey

During the Sihanouk era (past king) the area near Tompoun/Cheung Ek Wetlands was surrounded by woodland. People farmed, fished, and lived from the forest’s resources. In 1979, after the Pol Pot era, people returned from refugee and other camps to settle in PTK1. At this time there were a few houses in the village. Starting from 2000s, many people moved to inhabit PTK1. The area is attractive because is near to the city, people can go to work in the centre and grow aquatic crops for livelihood. Most people have moved from the rural villages and at this time they were able to buy affordable land. Presently, most people who buy the land are from Phnom Penh as the average lot size (6 m x 12 m) costs approximately USD $155,000.

Presently, there are about 360 urban poor families in PTK1. These families depend on the lake to sustain their livelihood. They also have emotional attachments to the area as they been living here for a long time. Since 2005 the ING company and other business people had bought land in the lake and infilled it. Many in-filled plots remain vacant and contribute to land speculation. Sand has been taken from the Mekong and Basac Rivers for this purpose. Ships are taking sand and storing it in Chak Angre Loeu and Chak Angre Krom pagodas. A pipe of about 60mts between Samdach Hun Sen Blvd and National Road 2 cuts across to fill-in parts of the lake in PTK1.

Local NGOs have implemented community organising and advocacy activities in PTK 1 since 2005 such as for land title registration and build community infrastructure. Thanks to the support from NGOs people in PTK1 have obtained land registration for their residence under the government’s Land Management and Administration Program (LMAP); however, many remain without an official land title document. Also, PTK1 community members are no longer allowed to lease plots along the lake to grow food and fish. There have been cases where security guards have destroyed farms in the lake without any prior notice to community members. Some of the original families living here have lost their land as they do not have access to aquatic crop plantation anymore and cannot pay their loans, so they have had to sell their land. Other families have sub-divided land plots and given these to their children. The people in PTK1 want to stay in the same place since they consider it as being safe for their children, they also have good local knowledge and good social connections. People also have access to school, health care centres, market, and can find jobs easily. Community people do not have any benefit from the development of the ING satellite city, especially poor people as all of them depended on the lake resources. To be able to survive, the majority of PTK1 community people have changed their job from aquatic farmers to motor taxi drivers, factory workers, cleaners and construction.

Community members have organised to demonstrate against the in-filling of the wetlands, and in some cases have been successful in stopping in-filling activities. Community members have received support from NGOs including training regarding the land laws and their land rights, advocacy strategies including engagement with local authorities, and activities to strengthen their spirit, learn to speak without fear, and psychological support to manage emotions. They have advocated to the Primer Minister and local authorities; however, people feel they can’t stop the development especially since the Prime Minister announced support for the development.

Prek Takong 2 (PTK2), Sangkat Chak Angre Loeu, Khan Meanchey

In 1979, PTK2 community was formed near a brick factory (now known as Orang garment factory) in PTK village. The brick factory workers lived in the main village and some families lived along a small road which evolved into PTK2 community. Since 2005, new people have come to live in PTK2 from different provinces and villages nearby. Different from their neighbours in PTK1, community people in PTK2 do not have land registration. Their land parcels were excluded from this process. The community is labelled as an informal settlement and their land demarcated as state land. PTK2 experiences light flooding from July to November. During the flooding season, people move to a safe area nearby. Recently the flood water level has been deeper than before. In 2018 two brothers aged 10 and 7 years old drowned as they walked to school.

The PTK2 community was organized by the NGO Urban Poor Women Development in July 2017, there are 3 women committees, and a total of 63 urban poor families. Most of the young women work in the garment factory and men work in the construction field. Some people are recycling pickers, food vendors, motor-taxi drivers, and workers in private companies. Some families run small grocery businesses in front of their houses. On average, people have an income of USD $2.5-10 per day. Some families have ID card and receive free healthcare.

Before, some families leased a plot in the lake area, where they grew morning glory, water mimosa, fished, and collected other resources from the lake. At the time people could use water from the lake as it was clean. Nonetheless, since 2012, the ING companies have started in-filling the lake. In 2013, local authorities tried to evict people from the PTK2 community but the community mobilised and it was not possible. In 2017, high-scraper buildings have been built. Also, a high fence has been placed along one side of the road where the community is located. For three years since they have started to build high-scraper buildings, people have experienced health issues due to pollution such as smoke from the generator, bad smells, dust, noise, and sometimes parts of iron or cement from the construction process.

This community is organised and has also received support from local NGOs. The community’s approach is to undertake ‘soft’ advocacy with the aim to collaborate with authorities as well as the private companies rather than opposing the development directly. People hope the authorities no longer consider their community as an informal settlement. They still advocate for building a proper road, get land title, and have access to clean water in their community.

Stories from everyday urban poor women

Mrs. Phat Sabau – SRT Community

Mrs. Sabau moved from her homeland in Prey Veng province to SRT village in 2000 because her family lost her rice field. One of her cousins gave her a plot of land next to the lake where her family established a simple livelihood. By living close to the lake her husband could fish and do aquaculture. During the Buddha’s holy day, she collects lotus flowers in the lake and sells these to people who make offerings to the Buddha. Also, she sells lotus root and seeds in front of her house. Her family earns an income of about USD $5-7 a day. Her husband and son fish in the lake every day. They have one motorboat to go fishing. Sabau also plants morning glory and has installed a small aquaculture net for raising fish behind her house. Every five to six months, her husband harvests fish from their aquaculture activities. Sabau takes the fish to sell them to retail sellers located about 3km from her place. She also makes prohok (Cambodian dish) and salty dry fishes for her family to eat. During the last two years Sabau has seen how the lake has been transformed by in-filling practices. Unlike before, the lake now has only a few small fishes. The flowers and vegetation have also declined. Because of this she could not collect aquatic flowers like in the past except the lotus flower which she plants. She expressed the important of the lake for her

“I feel Tamok lake is a historical lake, and it is very big lake, if it will be filled-in children would not know about the lake. The lake is our livelihood source where we can collect food in front of our house.

Mrs. Hang Sophal – PTK 1 Community

Mrs. Sophal is 63 and was born in Phnom Penh. She has six children. As most other people, after Pol Pot era in 1979, Sophal occupied a plot of land near in PTK1 village. In 1992, she sold the land for USD $500 to cure her husband’s illness and for her daughter’s wedding. She was left only with about USD $100 to buy a small plot of land near the lake. In 2008, she sold that land and rented a house nearby. Since she moved to live in PTK1, she leased a small area of the lake to grow morning glory and fishing with one of her daughters who lives in a tent next to her with her husband and two small kids. They grow morning glory and collect other aquatic plants in the lake to sell in the market. Sophal’s husband has a part-time job as a traditional music player in wedding ceremonies. In 2008, all her family could earn about USD $15 a day As a result of the wetlands in-filling activities by private companies in 2018, Sophal was told that she cannot lease any more area within the lake. Thus, she and her family started to work for their neighbours who still have a lease harvesting morning glory. In the same year, Sophal got diagnosed with a disease. Her income has dropped down to USD $3 per day and during the COVID-19 pandemic her husband was not hired for playing music in weddings. She has to request a loan from private money leaders who charge high interest rates to have some money for essential goods. She is sick and feels weaker every day. Tearfully Sophal said,

“I don’t want to live any longer, I wish I would die soon. I don’t want to live in hardship, get sick and hungry all the time.”

Sometimes, she and her husband don’t have food to eat so she must walk to the market to beg fish sellers to give her fish remains for cooking.

Mrs. Tim Phoum – PTK 2 Community

Mrs. Phoum is 58 and has four children, two boys and two girls. After married, Phoum bought a plot of land from her mother-in-law in PTK village in 1993. In 2005, her house and her neighbours went on fire. She lost all her belongings. Since then, her husband has got mental health problems and cannot work. Phoum sold her land and bought land

in Kandal province and a small plot in PTK2 community. She decided to buy this land because it was cheap, and not many people live there at the time.

Her neighbour gave her a plot land in the lake to grow morning glory and water mimosa. Phoum has dedicated since then to live from the lake and its activities, and she could earn up to USD $10 daily income. Since 2018 she has witnessed how the lake has been filled with sand. This has impacted on her livelihood activities and lead her to change her job as a part-time cleaner in a company. She earns more money but misses her way of life and relationship with the lake.

Stories from urban poor women leaders

Mrs. Sokhom – Leader STR community

Mrs. Sokhom is 49 years old, she cannot read or write, but has been a community representative in SRT community since 2018. She is respected by community members because she has dared to speak out and protest against the in-filling of the lakes and other threats of eviction. She always speaks with the truth and actions what she say will do.

When asked about her main achievements as a leader she explains it is to have the capacity to communicate well with local authorities. This has led her to negotiate positive outcomes for the community such as the construction of a community hall in an empty land plot. She has also helped community members to organise legal documentation to secure their land and being able to construct their houses.

Her experience as a leader has shown her that strong solidary between community members is the key ingredient to be able to achieve positive outcomes for urban poor communities. If there is participation and collaboration among the members local authorities cannot harm them. However, she mentions that most of the members in her community do not want to work together as this involves too much time and they do not see any changes regarding the lake in-filling. They feel powerless. She expressed,

“I am so stress and exhausted with my current work but due to a facilitation and encouragement from STT I can continue to deal with this work.”

Sokhom mentions that women play a very important role in leadership. For her the majority of women have the capacity to use soft and reasonable words, rather than a violent attitude that many men have during advocacy activities. She says,

“When the authorities blame us, I am very angry but I can control my ager and I know I should not show up my bad temper and response back to them because this makes it hard to communicate with them”

Sokhom’s hopes as a leader is that all community members can still live on their own land and have land title without any eviction.

Mrs. Lay Sreynet (Mao) – Community leader PTK2 community

Mao is 36 years old and a community representative in PTK2. At first, Mao was not so sure about becoming a community representative, but people believe in her because she helped them organised and they elect her. Mao also realised that she had a passion and willingness to learn about social issues. She has attended trainings from NGOs such as for environment cleaning, non-violent advocacy, land laws, and community savings.

Mao stated,

“when we advocate to local authorities, I always try to use very polite and soft words and control my anger, so I don’t show it to them”.

She mentions that the hardest thing as a leader has been to build trust among community members. At first it was quite hard since most of community members did not understand the meaning of working together but she tried to explain to them until they realised the importance of having a strong solidarity and started to participate more in community activities. Mao mentioned,

“there are some families who do not follow my leadership and instead try to destroy the reputation of the community doing things like selling drugs. But I will not give up as they are a part of this community, so I will keep trying to explain to them about the consequences of doing such illegal activity”.

Also, at the beginning Mao struggled with her relationship with men in the community. Men did not attend any community activities and thought this was not beneficial for their wives. But later, they encouraged their wives to attend. Mao specified,

“I highlighted to those men that all the challenges that we have in our community are common the issues and we really need strong solidarity to improve the current situation in the community. We need to be faithful and have genuine support between us”.

Mao expressed that it is very important for women to have leadership roles for urban poor communities. This is important because normally women lack power and influence, there is a very limited opportunity for them to participate in political and social matters, the local authorities do not value them and ignore them.

Mao’s wants to see a completely change for PTK2 community, so it is not considered a slum and can be officially recognised as a proper community with land title. She also hopes that the authority will happily cooperate with her without any discrimination like today.

References

1 Sahmakum Teang Tnaut (STT) (2019). The Last Lakes. Facts and Figures #40. December 2019. https://teangtnaut.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/STT-Facts-and-Figures-40-Last-lakes-_ENG_Final.pdf

[Accessed 16 December 2022]

2 Boudreaux, Karol. 2018. Intimate Partner Violence and Land Tenure: What Do We Know and What Can We Do? United States Agency for International Development.

3 Brickell, K. (2014) ‘The whole world is watching: intimate geopolitics of forced eviction and women’s activism in Cambodia’, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 104(6), 1256-1271

4 Sahmakum Teang Tnaut (STT) (2021) Boueng Tamok or Boeung Kbsrov. Facts and Figures # 43. April 2021.

https://teangtnaut.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/STT_Boeung-Tamok-report_ENG_Final.pdf [Accessed 28 November 2022].

5 Sahmakum Teang Tnaut (STT) (2019) The Last Lakes. Facts and Figures # 40. December 2019

https://teangtnaut.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/STT-Facts-and-Figures-40-Last-lakes-_ENG_Final.pdf

[Accessed 28 November 2022]

6 LICADHO, CYN, EC, STT (2020). Smoke on the water: a social and human rights assessment of the destruction of the Tompoun/Cheung Ek Wetlands. Report produced with the support of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights in Cambodia.

7 LICADHO, CYN, EC, STT (2020). Smoke on the water: a social and human rights assessment of the destruction of the Tompoun/Cheung Ek Wetlands. Report produced with the support of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights in Cambodia

Related Content

Posthuman Walking Project Podcasts

Posthuman Walking Project Podcasts By Dr Shirley Chubb and Dr Clair Hebron The following podcasts were compiled as part of the broader Posthuman Walking Project, which explores the entanglement of human and […]

Read More >