Trends of Definition of Landscape Phenomenon in Books Published Since Meiji Era in Japan

Yoji AOKI Abstract Recently, the difference of concepts between “Fukei…

“A more functional perspective quickly demonstrates that humans not only construct and manage landscapes, they also look at them, and they make decisions based upon what they see (and know, and feel). This dynamic helps to explain landscape structure as both an effect of culture and as an artifact that changes culture.”

Iverson Nassauer, 1995, p.230

Landscape shapes us, shapes our identities, shapes our relationships to nature and to our cities and shapes our understanding. Landscape is all around us shaping our daily lives, our sense of place, and belonging. But we shape the landscape as well. We play a role in shaping it particularly in urban areas where most of the landscapes are artificially constructed.

Cairo, the capital of Egypt, is a continuously growing city in the global south which faces an abundance of challenges and incessant urbanisation pressures. It is a complex system that contains multiple intertwined dynamics resulting in various perspectives and varied daily life experiences where one can feel an emotional roller coaster in one day or one trip! Cairo’s landscape reflects these complexities. It has multiple manifestations, dynamics, identities, and values that defies a simple explanation of what defines Cairo’s landscape. To unravel this query, multiple landscape manifestations shall be considered to shed the light on the various perspectives of landscape in Cairo. Ranging from the Nile River as a historical landscape element with cultural rootedness significance, to the social connotations of green spaces being exclusive entities and social images, to the economic stand on green spaces considered a draining resource and a burden on the governmental entities while also being promoted as an economic resource for individuals as in the case of green roofs, to the religious connotations of greenery as perennial charity. The manifestations of landscape in Cairo can be viewed on a passive active continuum as well, where green spaces are mostly dealt with passively as ‘see only’ entities in the cityscape and actively as an everyday individual hobby in the private realms to becoming a green activist.

“Egypt is the gift of the Nile.”

Herodotus, 4 BC

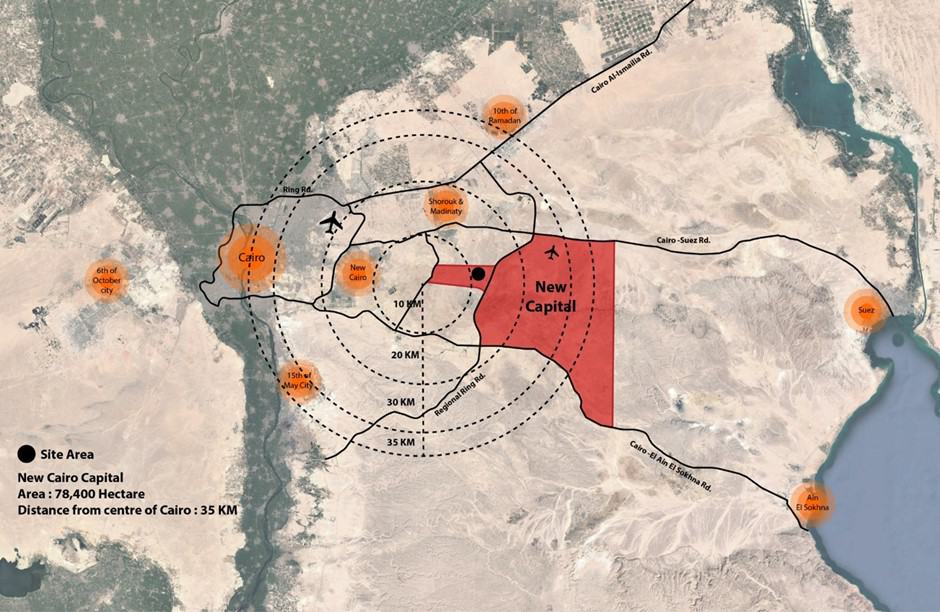

The Nile River has always been the main life support for Egypt. Since the early ages, ancient Egyptians praised the Nile River as the source of life and the gift of the gods. It has always symbolized life and lush in contrast to the harsh yellow deserts on its two banks. Cairo, as it is known nowadays, was established in the fifth century. Although it was established in the desert fortified with walls, the connection to the Nile and its greenery was not lost. There is evidence that supports the presence of lavish greenery inside the city walls and outside it surrounding the Nile where the residents used it as their recreational grounds (Rabbat, 2004; Pradines and Khan, 2016). Years and centuries passed by, and the Nile River still represents a significant cornerstone of Cairo’s identity to the extent that the new administrative capital, 70 km away from the Nile River in the Eastern desert of Cairo, shall encompass a ‘green river’. The green river is envisioned as a central green park crosscutting the new capital providing 7192 Feddan of greenery to represent the largest man-made green body that Cairo has ever witnessed.

In the 19th century, Cairo witnessed major development plans that added a new ‘Parisienne like’ morphology in contrast to the medieval morphology of Cairo city. Among the new developments were huge areas of parks and green spaces as private gardens for the khedivial palaces. These areas were exclusive to the royals and elites (Abdel-Rahman, 2016; Wanas and Samir, 2016). After the 1952 revolution, and the subsequent socialist and infitah eras, most of the green spaces were open to the public and today constitute most of Cairo’s green parks. These green parks charge tickets at nominal prices and attract lots of Egyptian visitors especially in the holidays such as Easter and Eid El Fitr.

“Historically, the first appearance of a modern public garden in Cairo, in 1837, was by fiat of Prince Muhammad ‘Ali. The pasha created for the public of Cairo (in particular, the European public) a promenade above Shubra Avenue. It transformed what was a swampy lake, Birkat al-Azbakya, into a park “in the European manner.”

Battesti, 2006, p.503

Exclusive landscape entities still exist in Cairo, with for example sporting clubs, gated communities, and parks that charge for access.

Following on from this tradition of exclusivity, the new developments in Cairo in the last 20-30 years (usually within the desert extensions on the peripheries of the city) utilise nature and green spaces as an attraction for people to leave the urban core of Cairo and to settle in the ‘desert’ (Abotera and Ashoub, 2017; Keleg, Butina Watson and Salheen, 2020). Most of these developments are pioneered by private real estate companies encompassing gated communities targeting high and high middle-income families. These gated communities offer a lifestyle that contrasts with the one offered in the dense core, through an abundant provision of villas with exclusive gardens and public greenery within the gates of the development available for the owners only. Living in one of these compounds is now being considered a social image of the higher strata of the community, living privately and exclusively within the gates among the greenery.

Following on the new liberal economic approach adopted by the current Egyptian government, there have been numerous debates on the feasibility of public green spaces in Egypt. The public green spaces are considered a financial drain and a burden on the government’s budget. Hence, many green spaces were invaded by food kiosks to create revenues by charging rent fees. Also, numerous parks are now being privatised, by offering parts or wholes for rent by the private sector, which usually implies raises in the entry tickets and would eventually lead to the gentrification of the users.

While high density areas within Cairo lack green spaces, there have been numerous initiatives and programs aiming at providing greenery into these poorer areas through roof gardening. Though most of these initiatives base their models on productive green roofs, where the residents either grow their own food or sell the produce. Usually, these initiatives are introduced in informal areas or low-income districts as a win-win solution offering greenery in very dense areas lacking any public area suitable for greening and offering an economic revenue for those in need.

While green roofs are predominantly for economic revenues, another value that motivate people to take part in greening is providing productive fruit trees in public spaces as a means of perennial charity. The availability of the trees allows people to freely access fruit, whilst contributing to the aesthetic scenery and fragrant smells to the city. As idealistic as these values may appear, in reality it is sustainably and practically highly questionable for various reasons, of which are the illegality of productive trees as per the local legislations of Cairo, the high level of air pollution in Cairo risking the toxicity of the fruits, and the stewardship of these trees in the long run (lack of ownership).

Almost all of Cairo’s green spaces are fenced, with many offering no access to the public. These restrictive measures are usually carried out by the responsible governmental agencies to minimise maintenance and management needs, combat criminal behaviour thereby passively reducing illicit behaviour and vandalism linked to deserted and unmaintained green spaces. This notion of ‘see only’ landscapes has extended to the gated communities as well. The high maintenance fees paid by the residents to the gated communities’ management encourages the residents to police each other to prohibit using the green spaces in order to maintain their cleanliness, and to reduce the wear of the lawns and the greenery.

In a city lacking public green spaces with minimal and tightly censored public realm activities, balcony and roof gardening is rising as a green hobby. Despite the small area of these balconies, the close everyday contact with plants provides ecological knowledge to the participants, which is severely lacking among Cairo residents leading to major human-nature disconnection.

The current changes to the cityscape of Cairo has resulted in the widespread destruction of trees and continuous encroaching privatisation of green spaces. There are however some local activists who are fighting for the survival of green spaces in the city, as far as their efforts and powers allow. Multiple groups in various areas of Cairo are fighting to keep people’s rights to greenery by saving the little that is already there. Some of these efforts come from organised associations and organisations, some have legal standings and manifestations while others are individual grassroot efforts. The common thread among all the various efforts is their strong belief of the true value of greenery and people’s rights to green spaces, especially in a dense city such as Cairo.

Amid all these varying perspectives on landscapes, it is clear that there is not ‘one’ definition of landscape in Cairo. Rather, it is who you are, where you are, and how you encounter landscape in your daily life in Cairo that shapes your personal perspective and creates your own definition of the landscape.

Abdel-Rahman, N.H. (2016) ‘Egyptian Historical Parks, Authenticity vs. Change in Cairo’s Cultural Landscapes’, Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 225, pp. 391–409. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.06.086.

Abotera, M. and Ashoub, S. (2017) ‘Billboard Space in Egypt: reproducing nature and dominating spaces of representation’, The Urban Transcripts Journal, 1(3), p. Online.

Aly, D. and Dimitrijevic, B. (2022) ‘Public green space quantity and distribution in Cairo, Egypt’, Journal of Engineering and Applied Science, 69(1), p. 15. doi:10.1186/s44147-021-00067-z.

Battesti, V. (2006) ‘Reappropriating Public Spaces, Reimagining Urban Beauty’, in Cairo Cosmopolitan: Politics, Culture, and Urban Space in the New Globalized Middle East. The American University in Cairo Press, pp. 489–511.

Iverson Nassauer, J. (1995) ‘Culture and changing landscape structure’, Landscape Ecology, 10(4), pp. 229–237. doi:10.1007/BF00129257.

Keleg, M., Butina Watson, G. and Salheen, M. (2020) ‘Public Perception of Environmental Change in Rapidly Growing Cities: the Case of Cairo, Egypt.’, in SHAPING URBAN CHANGE – Livable City Regions for the 21st Century. REAL CORP 2020, 25th International Conference on Urban Development, Regional Planning and Information Society., ISOCARP, pp. 677–687.

Pradines, S. and Khan, S.R. (2016) ‘Fāṭimid gardens: archaeological and historical perspectives’, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 79(3), pp. 473–502. doi:10.1017/S0041977X16000586.

Rabbat, N. (2004) ‘A Brief History of Green Spaces in Cairo’, in Bianca, S. and Jodidio, P. (eds) Cairo: Revitalising a Historic Metropolis. Turin: Umberto Allemandi & C. for Aga Khan Trust for Culture, pp. 43–53.

Wanas, A. and Samir, E. (2016) ‘Social Mobility and Green Open Urban Spaces’, 10(1), p. 14.