Limestone flows. At a geologic pace, it seeps and pools. It gets absorbed and expressed. It even upheaves and depresses daily with the tide.[1] Our most solid and stable substance, rock defies the linguistic bounds we place on it, exceeding our expectations and acting according to its own logic.[2] This defiance, a refusal of easy categories, forces us to confront the inability of our thinking to capably describe the more-than-human world. The very notion that rock has a sort of behavior forces thoughts that are dizzying and vertiginous—uncanny, even.[3] What would seem fantastical or metaphorical is in the end scientific fact. Such realizations make us feel like the ground beneath us is shifting, and that unsettling feeling is ever more familiar, accelerated as it is by the climate crisis. If even stone can speak, in a way, then climate adaptation—learning to live on a changed planet—requires that we[4] get accustomed to the disquiet. We might even learn to listen.

This is a story about deep time comingling with the future. It is about a present in crisis, shaped by historical contingency as well as the coming indeterminacy. While it starts here with limestone and its permutations, it is not exactly a story of geology. Rather, it is a properly ecological tale about the liveliness of the places we inhabit and the practices that can lead us to recognize our relationship to those places. Its main character is the lowly oyster.

I arrive at the Annisquam expectantly. The river is the most travelled in Massachusetts, dredged occasionally for navigability by the Army Corps of Engineers. It has been a site of human modification since before European colonization. Terraformed bridges, once used to aid native fishing and shellfishing, are still evident in the landscape. The Annisquam bisects Gloucester, Massachusetts, separating a residential shore from my destination in the commercial downtown. I have come to this working waterfront because, for months, I have been hearing about an ecological restoration project here, and the two biologists responsible have agreed to meet me.

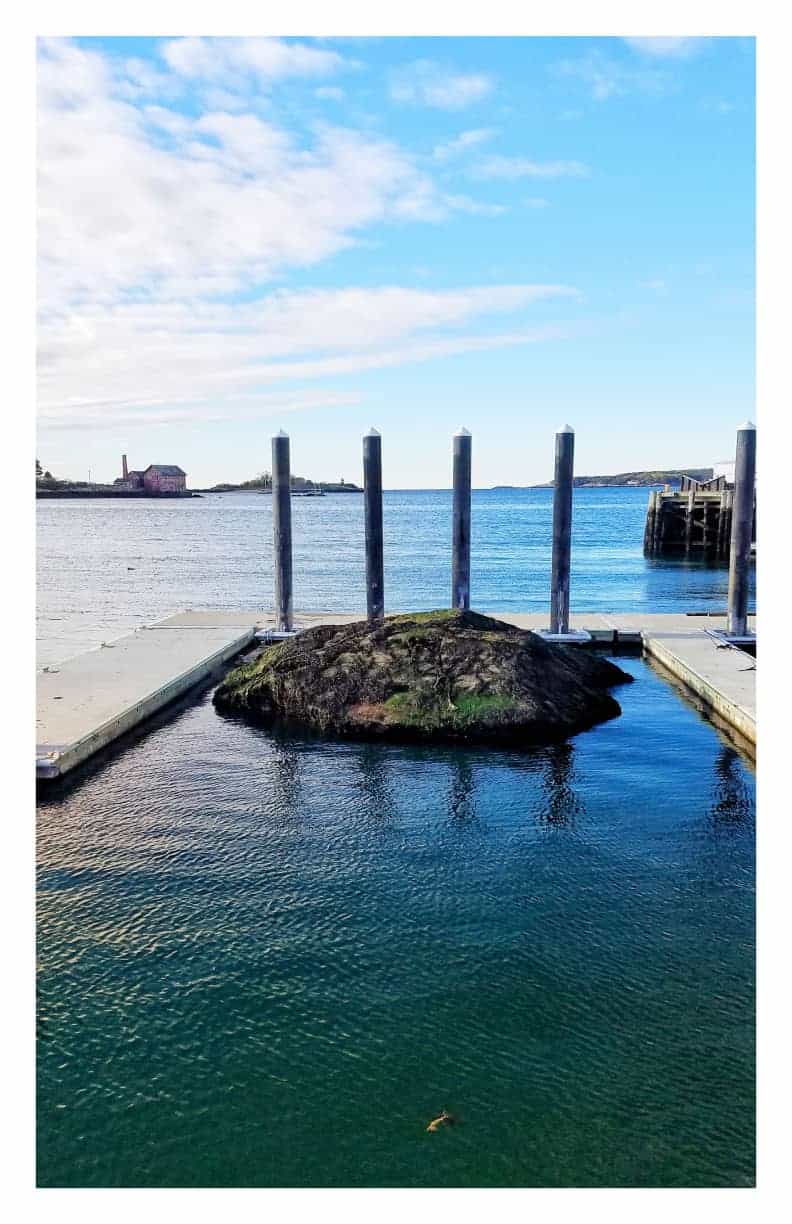

It is low tide when we gather on Gloucester Pier. It is late autumn and workers are readying the tour boats for winter. Few people can be seen. We’re outnumbered by seagulls sailing high on strong winds that drove off last night’s storm clouds, replacing them with a reflective cirriform cloudscape and a starkly bright New England day. For over two hundred years, Gloucester’s harbor front has been an active industrial site. Piers jut out into the harbor. A fishing boat returns from beyond the mouth of the inlet, passing me and the empty moorings whose boats I see shrink-wrapped and stored on the other side of the water.

Elsa[5] finds me first. She’s young, just out of college, and effervescent. A marine biologist by training, she’s the sole staff member on a project to seed the Annisquam with thousands of baby oysters. Crassostrea virginica, the Eastern oyster, disappeared from Gloucester’s waters long ago, a casualty of overfishing and poor water quality. Now, Elsa and her compatriots are working to restore the species. She sits on the edge of a tank wrapped in green tarp, the key piece of equipment for the restoration process, and explains. Young oysters, or spat, were gathered from a wild population in the spring and transported from the Gulf of Maine. They took up residence in the tank—called an upweller—where Elsa cared for them, ensuring proper growing conditions. The upweller is only a preliminary part of the process. After several months, the oysters were relocated to the river, where we will soon find them today.

Dana arrives with her son, Tristen, in tow. We exchange greetings and note the tide gauge attached to the pier. We timed our arrival to improve our chances of finding the newly seeded oysters in the river; at high tide. There is no earthen path to where we’re going, only water. The Atlantic is just beginning to return to the Annisquam, so we drive, following the oysters’ path to their new home at the river’s edge.

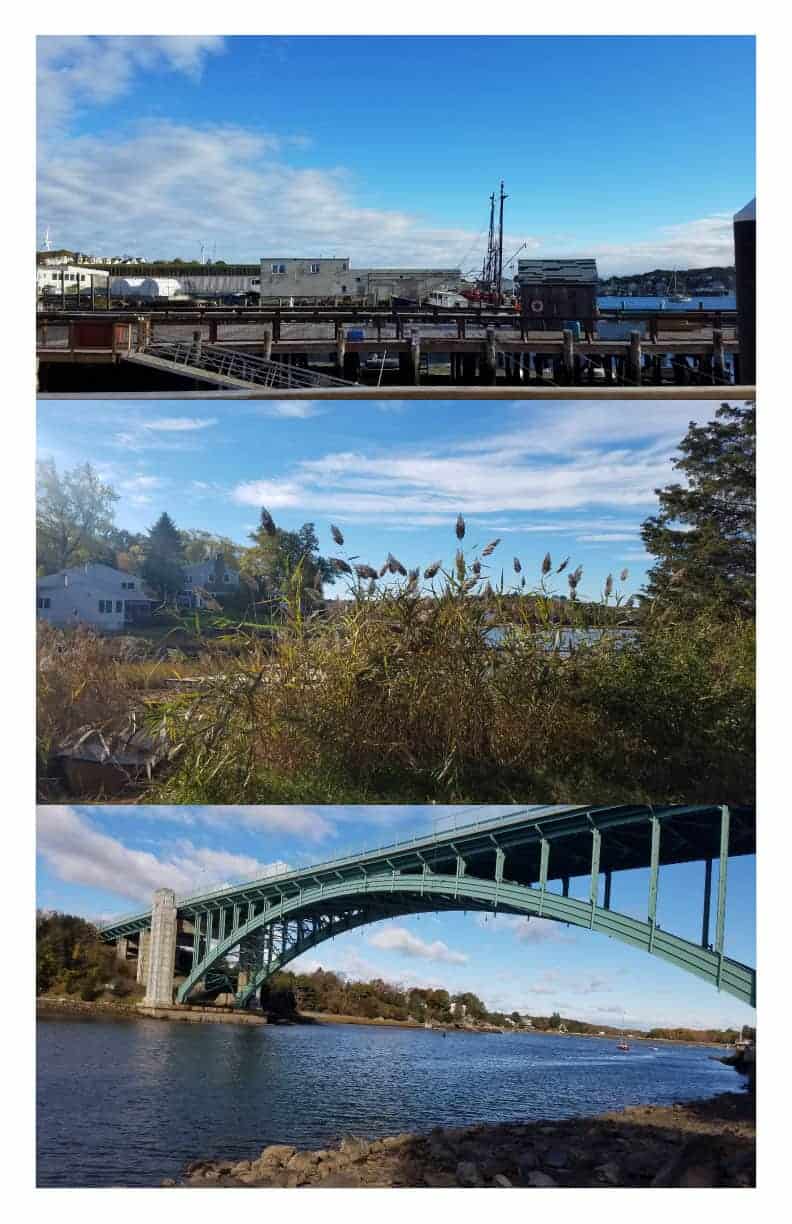

Pavement gives way to dirt roads as we approach. Trees thicken, most stripped of their leaves. Gloucester’s coast is densely developed but these young forests hide it well. We stop at a sandy lot at the edge of a marsh. It feels residential, like we’re liable to be scolded for trespassing, and that’s by design. Permitting any shellfish restoration project is notoriously difficult in Massachusetts, and inaccessibility was requisite to this site’s approval. There is no signage here, no indication that the long-missing oysters have recently returned. Their presence is obscured to appease state bureaucrats ostensibly fearful of the blowback from someone getting sick by an illegally harvested oyster.

The purpose of this project is threefold: to improve water quality, increase the diversity of sea life, and mitigate the effects of climate change. Oysters are filter feeders, and in the course of their normal activities capture waterborne contaminants and sequester them in the seabed. Their reefs attract hundreds upon hundreds of critters, from bacteria to birds. And increasingly, reefs are considered an alternative to seawalls for their ability to slow wave action and attenuate flooding from the rising seas.[6]

Our conversation picks up where it left off. Dana tells the oysters’ origin story again, this time to explain that an oyster farmer supplied the spat from the wild, and to the wild they’ll return. The oysters spent the last few months in a tank, but Dana never considered them captive or domesticated. Instead, aided by their hands, the new population will eventually grow wild in the Annisquam, surrounded by human roads, bridges, boats, and houses.

She never mentions the word wilderness, I notice. It strikes me how different her description sounds from other conservation efforts. For decades, centuries even, conservation embraced the idea that wilderness was where humans were not. It was untouched and pure, preserved in parks and reserves as a counterpoint to society. But to Dana, wildness happens just as easily right under our noses as it does at a mythologized distance. She is working to increase the wildness of an urban ecology. Hers is a wildness without wilderness.

There is another striking contrast hiding in her description. Restoration efforts are benchmarked, given success metrics that often borrow from a wilderness conservation mindset. A pre-colonization (often mistaken for pre-human) population is a typical goal. Dana, though, expects the oysters to become a sort of ecological infrastructure. She cares little for achieving a mythic landscape from the past and instead is focused on attracting a self-sustaining oyster population. She is restoring the future ecology of the Annisquam.[7]

We head down a small path lined with rocks to the marsh, then weave around boulders covered in seaweed and barnacles for a few hundred slippery, treacherous feet. Here at the water’s edge the land divides sharply between the riverbed and a forested hill that rises steeply to someone’s home. The slow force of erosion is stark and immediate. Glacial activity shaped this area at the end of the last ice age, and human land use—itself not unlike glaciation—has dug and rerouted the river.[8] A steely wind whips at us, funneled under the massive green arch bridge that looms overhead. Traffic noise drowns out the lapping water and we huddle up to hear. Sediment stirred up by the wind and last night’s storm has clouded the waters. Dana worries that many of the nickel-sized baby oysters will be buried and lost.

We protect one another from the gusts, soon abandoning our hunt. Elsa walks me through how she chose this site for their work. There are the technical details she picked up from her training as a marine biologist. She knows about the oysters’ preference for certain types of substrate (rocks and shells) and water quality (low salinity, low flow). She had consulted the state shellfish habitat maps and narrowed down options based on these criteria. More than that, though, she tells me that she is now practiced enough to simply read a landscape and determine how an oyster would fare in it. To Elsa, an oyster’s world is more than shell and tissue, more than the plankton they consume and the water they pass through their tiny bodies. It has been constructed by the oysters, but also by their interactions. Crassostrea virginica is situated on the banks of the Annisquam with other animals/plants/people/things[9] that give their world definition. Oysters are as much a part of the landscape as they are engineers of it. Their world is a landscape phenomenon, and it is legible to Elsa; her understanding of an oyster’s needs is an understanding of its relationships.

Back in the sandy lot, we stand behind a wall of Phragmites that buffers the wind. The sun warms us and Tristen reaches for pebbles to dunk in a rainwater puddle. We talk shop a while, about other oyster restoration projects in the region and the difference they are making in their respective ecologies. There is a functional role the oysters play, we agree, but Dana and Elsa’s words suggest something more. They see themselves as caretakers and the oysters as engineers. The shellfish have a sort of agency that relegates human control over the project. Pragmatically, materially, the oysters are partners in the work. They are living beings with their own drives and interests. They will do their thing no matter what, Dana tells me, and what they will do is all the work—improving water quality, constructing habitat, and protecting the shoreline. In her experience, caring for oysters means recognizing their agency and involving them as active participants in making infrastructures.

Together with Crassostrea virginica, Dana and Elsa’s work is to fine-tune the coordination of the estuary, to be involved in the making of wildness and infrastructure simultaneously. A modern restoration effort might stop with a successfully reasoned plan to repopulate the species, but for these biologists the focus is not on the oysters alone but the dynamic and agentic landscape of which they are a part.

Just as we are about to part ways, Dana suggests that I have a look at the state shellfish regulations to see if I might find a way to encourage more projects like theirs. They are onerous and designed to favor the shellfish industry over restoration or climate adaptation interests—let alone the oysters themselves. There should be an exception, she thinks, to the rule against keeping permanent populations of oysters off limits to harvesters. This would allow Crassostrea virginica to return on its own terms. I take her proposal seriously but will only come to realize its implications months later. The oysters’ role in infrastructure work puts them in the climate adaptation planning discussion, and our task as planners, designers, and policy makers will be to treat the ecologies we inhabit as partners in the making of infrastructure.

Environmental policy and urban planning urgently need to recognize the liveliness and materiality of the more-than-human world, for the sake of our shared survival. Nature-based infrastructure, a term of art for projects like Dana and Elsa’s, offers one such opportunity. Compared with other forms, nature-based infrastructure (NBI) most readily admits the hybrid and lively character of climate adaptation infrastructures. Unlike traditional conservation efforts, NBI does not seek to preserve a stable realm of nonhuman Nature apart from human society, but to jointly produce ecologies that are dynamic and experimental. In this sense, NBI is hybrid, a natural-cultural composition. Other species are actively involved in continuously making the infrastructure, and the success of any project is predicated on the nature of the relationships amongst agents. NBI is thus lively; it involves the lives of other beings and our own ways of living. It is flexible and adaptable, allowing for continuous experimentation and ever-changing encounters. More than that, it combines and choreographs different ways of being in the world: as scientists and planners, among oysters, trees, microbes, and many others involved in the same multispecies effort.

A shift to multispecies planning, as I have come to call the political elements of this choreography, requires being open to other forms of knowledge and expertise, not all of which is human. To plan with the nonhuman, we first have to take stock of our surroundings. It starts as Dana and Elsa did, with a full accounting of the animals/plants/people/things in the landscape, then moves to an analysis of their respective needs and the relationships built to meet them. Multispecies planning also considers the temporal contexts in which a landscape is situated. The land use history, geomorphology, and expected climatic shifts are all relevant to multispecies planning decisions.

Multispecies planning treats scientific knowledge as one way among many of coming to know the experience of other beings. Appreciating nonhuman knowledge requires that we attune ourselves to the needs of other species with whom we share habitat and adjust our knowledge claims accordingly. One comes to know elephant land use practices, for example, by being with elephants in the landscape. This attunement is often more than a rote skill. Conservationists have a particularly evident affective relationship with the landscape and other species in it. They enjoy the work for its aesthetic value and come to literally embody the fact of their relationships by tuning their senses to their surroundings, just as Elsa could know an oyster’s chances of survival simply by being in the landscape. Science is a privileged means by which their appreciation develops because it has the capacity to describe nonhuman worlds—what it feels like to be a bee, or a blade of seagrass—but it is not the only form of knowledge that multispecies planning requires.

Having parsed these thoughts, I returned to Dana’s request to adapt our shellfish policies to her reality of partnering with oysters. I found that the hurdles she encountered resulted from a complex policy environment, including meeting federal shellfish industry regulations, state-level waterfront access and management laws, and municipal needs as determined by the local shellfish constable. The laws are intended to minimize public health risk from shellfish consumption and to guard the industry against the consequences of trading in contaminated shellfish. Overall environmental health is discounted in favor of anthropocentric health and trade policy.

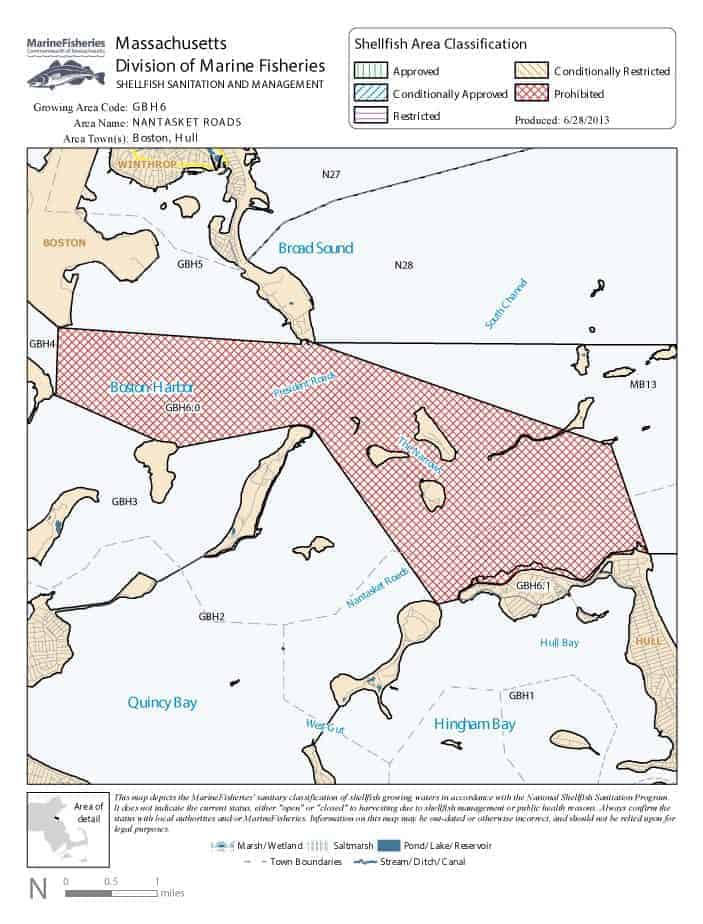

Perhaps the most apparent show of this limitation can be seen in how oyster habitat is regulated and policed. The Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries (DMF) is responsible for charting the jurisdictional boundaries within which the ocean’s water quality is evaluated. When levels of contamination are too high in a given area, such as the Annisquam, DMF restricts or closes shellfishing.[10] Indeed, the division will sometimes resort to relocating shellfish to cleaner waters. Additionally, by right, the people of Massachusetts have equal access to fish, fowl, and navigate along the coastline—including to shellfish.[11] No shellfish population can be permanently restricted from harvest, including for restoration or climate adaptation purposes. The project in the Annisquam was permitted for research and education purposes, but it was in a double bind when it came to its goal of reestablishing the river’s wildness. The very reason that Crassostrea virginica was so badly needed there meant that the site was perpetually off-limits to shellfishing, in violation of state law. Perhaps worse, if they were successful in achieving a self-sustaining population, the oysters ran the risk of forced relocation.

There were two conflicting topologies[12] in play: one wild, one regulatory. There is the possibility, however, of reconciliation. A multispecies planning approach to the state shellfish guidelines would allow wild oysters to populate in contaminated waters, to permit humans to facilitate and steward the process, and to encounter oysters as infrastructure, rather than exclusively as a commodity. It would also allow for the continued regulation of harvests to prevent public health harms. Rather than being in the business of limiting ecological interactions and preventing changes, a Division of Marine Fisheries that relied on this form of knowledge would observe and assess ecological flux.

Embracing a wild topology in a regulatory framework is a potential solution for the biologists and oysters whose infrastructure populates the Annisquam. It is also demonstrative of the approach to planning and policy that climate adaptation demands. If we limit the potential of nature-based infrastructure to technocratic, economistic concerns, we will miss the opportunity to diversify the forms of knowledge that we need for addressing the climate crisis. After all, changing the way we interact and think with nonhuman others is itself a critical form of climate adaptation.

A distinguished urban ecologist and professor once told me that to understand ecology one must learn to see the world from the point of view of a plant. Another told me that grasping hydrology depended on one’s ability to approach the issue like a raindrop. The renowned 20th century conservationist Aldo Leopold urged us to think like a mountain. Aphorisms like these abound in environmental thought and open on to new ways of knowing the world. Crassostrea virginica, the Eastern oyster, offers its own lessons in climate adaptation, borrowed as much from the future as from deep time. The long erosion of limestone into seawater has enabled shellfish to construct shells of calcium carbonate. The oysters’ reef-building habits turn old limestone into barriers that will protect seas and shorelines from anthropogenic harms, and with that, human settlements. If there is hope, it is here, not in the declensionist narratives of a near miss with extinction and ruin. We need only start from a different place—to assume an oyster ontology—and whole worlds open up. Dana and Elsa’s work suggests that this strange coincidence of futurity and historicity, and of the human and nonhuman, only seems strange because we’ve gotten used to denying it. The world was always already this way; we’re just coming to notice.

References

[1] Earth tides have been theorized since Charles Darwin’s time and known in more detail since the 1960s. The tides have short cycles of roughly 12 and 24 hours, and long-term cycles of up to almost 19 years.

[2] Cohen, Jeffrey Jerome. 2015. Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

[3] Ghosh, Amitav. 2016. The Great Derangement. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[4] By “we,” I mean those of us Bruno Latour would refer to as moderns: those for whom the disavowal of the hybridity of nature and culture is a central conceit. Not everyone sees the world this way. There are examples from all over that run contrary to this definition, notably many indigenous lifeways.

[5] Names have been changed to protect the institutional review board.

[6] There is strong scientific support for the first two claims. As for shoreline stabilization, the jury is still out. Scientists treat findings as generally positive but not unequivocal. For more, see: Morgan, David. 2019. “Multispecies Planning: Locating Nonhuman Entanglements in Oyster Restoration Policy on the Massachusetts Coast.” Tufts University. http://hdl.handle.net/10427/PK02CP74Z.

[7] Keith Bowers of the US-based ecological restoration firm Biohabitats popularized the saying “restoring for the future.”

[8] I owe the analogy of human activity as glaciation to the ecologist and professor Peter del Tredici.

[9] This turn of phrase is borrowed from: Ogden, Laura, Billy Hall, and Kimiko Tanita. 2013. “Animals, Plants, People, and Things.” Environment and Society: Advances in Research 4: 5–24.

[10] DMF is required to create some form of regulation to protect against shellfish-borne illnesses through the state’s voluntary participation in the National Shellfish Sanitation Program, which regulates interstate trade of shellfish.

[11] The law granting these rights is called Chapter 91. It is a codification of the Colonial Ordinances of 1641-1647 and a treasured part of the state’s culture as it affords recreational and conservation opportunities and protects against private development.

[12] In geography, topology has been employed to show whether spatial relations conform to Cartesian expectations, and how the literal shape of the landscape is historically determined. The concept is borrowed from mathematics, where it is a technique for determining the conditions under which geometric figures or spaces will change form.