Rewilding the Popular Imagination: An Analysis of Key Themes in the Visual Communication of Rewilding to a Wide Audience

Dr Jo Phillips, Manchester School of Architecture

Rewilding the Popular Imagination: An Analysis of Key Themes in the Visual Communication of Rewilding to a Wide Audience

Dr Jo Phillips, Manchester School of Architecture

Introduction

This research is a pilot study that explores perceptions and communication of rewilding in the UK, using three methods. These are;

- a three-part review of literature and visual materials exploring concepts relating to wildness and rewilding, and the challenges of communicating those concepts to a non-expert audience,

- interviews with practitioners in the field of rewilding,

- a survey of people’s preferences for photographs of landscapes undergoing rewilding. The survey aims to test an approach that could help researchers to understand how positively or negatively people perceive different degrees of human presence in photos, with a view to informing approaches for communicating rewilding projects to relevant audiences.

The literature review and interviews were undertaken as an iterative process, so that interview participants’ views guided readings, and vice versa. The research was done with the help and support of experts in the field of rewilding, who are not academics. They bear direct responsibility for the future ecological health of parts of the UK, in particular in rural areas which have previously, or which continue to be, farmed. They guide the success on the ground of rewilding processes, a crucial element of which is negotiating the acceptance of these projects in a challenging social, economic, and cultural context. The importance of these rewilding communicators and managers to this research means that this paper has been written with a dual audience in mind: both academic and expert non-academic.

The potential scope for research in this field is very large, because, as the UK government now recognises, the environmental and social challenges faced in our rural landscapes are significant, particularly with respect to biodiversity and connecting people with nature (DEFRA, 2021). Increased biodiversity and wildlife recovery are the key aims of rewilding projects, against a background of 13% decline in average species’ abundance in the UK between 1970 and 2019, with 15% of UK species classified as threatened with extinction and 2% already extinct (Hayhow et al., 2019). This is within the global context of approximately one million plant and animal species being threatened with extinction in 2019, and 23% of the world’s land area seeing a reduction in productivity due to land degradation since 1970, in part due to a threefold rise in food crop production in that period (IPBES, 2019). This is happening as we see an increasingly urban global population in which many people will have only limited daily contact with non-human nature (Beery, Ingemar Jönsson and Elmberg, 2015). This paper is founded in the belief that we have an ethical imperative to rewild a proportion of agricultural landscapes, due to the intrinsic value of species diversity, the rights of nature (Maffi, 2007) and the clear benefits to human health, happiness (Natural England, 2019) and perhaps survival.

This research is small in scope and raises many more questions than it answers, but it aims to be a starting point for discussion between researchers and practitioners about the communication of rewilding to different audiences, using visual media as a focus. The focus of the work is to explore the concept of rewilding and to draw from this process some key themes which could be used as a framework for visual communication of rewilding projects. Put simply, what should our priorities be when communicating rewilding to the public?

Literature Review Part One: Current Concepts of Rewilding in the UK

‘Rewilding’ is a controversial term because, for some, it is perceived to imply a desire to return a landscape to an impossible idealised state, before any human occupation of that place, and can consequently sometimes be framed as anti-human. This prompts a fear that an established human relationship with cultivated land, including centuries-old management skills as well as psychological and social connections, could be lost (Levitt, 2021). Additionally, the term has been problematized by concerns associated with the reintroduction of top predators (Pettorelli et al., 2018), particularly wolves but also wild cat species such as lynx (Wilson, 2004; Enck and Bath, 2012), and raptors like the sea eagle (O’Rourke, 2014), all of which can be seen as threats to rural income streams, as it is feared that there will be significant losses of livestock and game birds. In addition, landowners may fear a decrease in the value of agricultural land if it becomes recolonised by scrub vegetation and trees (Case, 2018). It is also possible that the very idea of processes being restored as an end in themselves, without quantifiable aims against which to measure success, is a problem for acceptance by people used to operating in our target-driven culture (Corlett, 2016).

Despite these concerns, rewilding has begun to take root in the UK as a promising strategy to enhance biodiversity (Pettorelli et al., 2018), and also, in some places, as a foundation for a successful rural enterprise. The best-known example of this is perhaps the Knepp Wildland project in West Sussex, which began in 2001, initially as a strategic response to the deteriorating fertility of the soil, and falling crop yields as a result of intensive farming methods over many decades (Tree, 2019). Increasingly, as the project has succeeded in many measures, it has developed as a celebration of the greater abundance and range of species on the estate. It has also, crucially, captured the public imagination and become a successful eco-tourism business. The success of Isabella Tree’s book about Knepp (Tree, 2019) has to some extent raised public awareness about the effects of intensification of farming methods in recent decades (Jepson and Bythe, 2020), which has come to be recognised as “the most important driver of biodiversity change over the past 45 years, with most effects being negative.” (Hayhow et al., 2019: 19). That rewilding has entered the public consciousness is also evident across a range of popular nature and horticulture writing for both adults and children (see for example National Geographic Kids, 2022). In Scotland the topic is particularly high on the agenda, with a poll by the Scottish Rewilding Alliance in 2021 finding that 76% of Scots support ‘the large-scale restoration of nature to the point where it is allowed to take care of itself’ (Amos, 2021).

The meaning of the word ‘rewilding’ logically implies a return to wilderness, a concept which has been an ‘ideological battleground’ since the beginning of European colonisation of North America (Taylor, 2012). Wilderness has arguably come to be seen by dominant cultures as being wasted land, in opposition to cultivated landscapes of agricultural plenty, with farming being valued as the very basis of civilisation (Taylor, 2012). The proposal of the concept of rewilding has been documented as emerging in the 1980s, with rewilding as a specific scientific term first used in 1991 in relation to the North American Wildlands Project (Jørgensen, 2015). The term has been used with multiple meanings over the last three decades, possibly resulting in undesirable complexity and confusion about its ecological aims (Carver et al., 2021). Additionally there may be multiple culturally specific modern interpretations of the word wild and of the desirability or otherwise of wildness, the meaning of which shifts over time (Jørgensen, 2015). Growing support for rewilding nevertheless seems evident, with one particular prediction that the term itself will “gain ascendancy over ‘conservation’ and ‘environmentalism’” (Jepson and Bythe, 2020: 150).

Rewilding as a scientific method has been developed by ecologists since the late 1990s, based around core principles of large interconnected areas of land where species are protected, and keystone animal species reintroduced (Carver et al., 2021) in order to restore desired relationships between predators, prey, vegetation, fungi and soils (Jepson and Bythe, 2020). The reduction of human intervention to a minimum is important, so that complex ecosystem processes can eventually become self-sustaining (Pettorelli et al., 2018). Rewilding is not the same as conservation or restoration of specific habitats or species, in that the key to its success lies with the unpredictable flourishing of natural processes, and the ability of nature to thereby gradually recover itself (Simard, 2021). Restoration implies returning a landscape to a specific prior state, or baseline, in which patterns of habitation by particular species were fixed in a known ideal condition. This is problematic, in part because there may be more than one possible baseline that is considered desirable (Jørgensen, 2015), but also because global environmental change is driving ecosystems beyond their sustainable limits so that restoration to historical benchmarks or modern likely equivalents may no longer be an option (Pettorelli et al., 2018). Rewilding, as it is currently understood, does not usually aim to restore specific species in this way. Instead, practitioners emphasise the flourishing of ongoing processes (Monbiot, 2014) over specific targets for outcomes. The full flourishing of these processes is commonly accepted to be reliant on keystone species (Jørgensen, 2015), including, in some places, large herbivores and carnivores, for their ability to reprogramme food webs and to manage the land, such as with beaver reintroduction to create wetlands and improve plant species richness (Law et al., 2017). The emphasis that rewilding projects place on reinstating natural processes has the potential to be a more resilient response to the inevitable but unpredictable changes the planet faces (Weber et al., 2014).

This paper will understand rewilding as the recovery of ecological processes, sometimes called ‘ecological rewilding’ (Pettorelli et al., 2018; Corlett, 2016), but acknowledges the multiple other meanings which may exist in the general consciousness, and which complicate the task of communicating rewilding to non-experts. An additional factor of this challenge is ‘shifting baseline syndrome’, a term first used by fisheries scientist Daniel Pauly, to explain perceptions of depleted fish stocks, where each successive generation of observer assumes the baseline for a species population to be what it was at the start of their career, so that each new generation assumes that the depleted stocks are in fact the (desirable) baseline (Pauly, 1995; Vera, 2009). This is frequently demonstrated in attitudes to rural agricultural landscapes in the UK, where sheep or deer grazed uplands are assumed to be the ‘natural’ state, because they have been the same throughout a human lifetime, and several lifetimes before that, when in reality they may be significantly depleted ecosystems (Monbiot, 2014; Fairbrother, 1970; Schofield, 2022). People may not wish to accept that landscape is constantly undergoing a process of change, that it may have been richer and more diverse before they were born, or that it could be so again after their life span. This difficulty can mean that people tend to hold relatively recent cultural and economic practises, such as agricultural traditions, as being of greater value than biodiversity in the landscape. Contrary to this belief, it may well be that in the relatively recent past, previous generations of local people operated a much more resilient local economy in which each farm produced smaller quantities but a greater range of produce for largely local consumption (Schofield et al., 2020) and with a lesser negative impact on biodiversity and landscape.

From other perspectives the term rewilding can be used to refer to discontinuation of agricultural management of land, ceasing production of arable crops and using domesticated animals on a small scale in order to disturb the seed bank in the soil and speed up recolonization of farmland by plant species. Some current UK examples of this also involve the production of meat, for example at Knepp and at Wild Ken Hill in Norfolk. This can usefully demonstrate to surrounding farming communities that income streams from food production can still be had from land undergoing rewilding processes, and act as an exemplar to encourage landowners to change their management strategy. This market-orientated approach continues to conceive of nature as an economic resource (Weber et al., 2014) albeit alongside a recognition of the intrinsic value of wildlife and biodiversity.

Most recently, common use of the word rewilding has broadened significantly, to describe a change in the maintenance regime of small areas of urban land, such as the verges of main roads, or distinct areas of public parks (Reading Borough Council, 2021; Yeo, 2021). In such examples, reducing the mowing of grass to perhaps once a year, often so that seeded flower species can flourish, will cut costs, raise public awareness and provide some insect habitat. This approach to management does not fall within the definition of ecological rewilding as it requires regular ongoing maintenance by people, albeit with a light touch. Rewilding projects and organisations typically present themselves as responding to species loss and the threat of mass extinction due to the climate crisis (Scotland the Big Picture; Rewilding Britain; Rewilding Europe). The term ‘urban rewilding’ is sometimes applied by the media to examples such as Manhattan’s high-maintenance High Line (Sturgeon, 2021), or architect Stefano Boeri’s Bosco Verticale apartment blocks in Milan (Malloy, 2021). Such coverage can be accused of greenwashing (for example Kohlstedt, 2016) by invoking the idea of rewilding to make new infrastructure seem environmentally acceptable, or even beneficial, when any new built form will in fact impinge on natural systems (Firth et al., 2020).

This diverse usage of ‘rewilding’ redoubles the challenge of communicating a scientifically complex concept to a non-specialist audience. However, the overarching theme present in all of the mainstream concepts of rewilding is the importance of process, requiring an understanding that rewilding does not have a pre-determined end point or target. Rather it is ongoing, dynamic, uncertain, and beyond human control. This is a key idea because this is the very nature of the ‘wild’ itself. It is one that can be difficult for humans to accept, as we may be more comfortable with the notion that we are in control of ‘our’ landscapes. This is the first key theme identified through this research: open-ended processes.

Literature Review Part Two: Humans As Nature

“A system is ever changing because its parts – the trees and fungi and people – are constantly responding to one another in the environment. Our success in co-evolution – success as a productive society – is only as good as the strength of these bonds with other individuals and species.”

Simard, 2021: 189

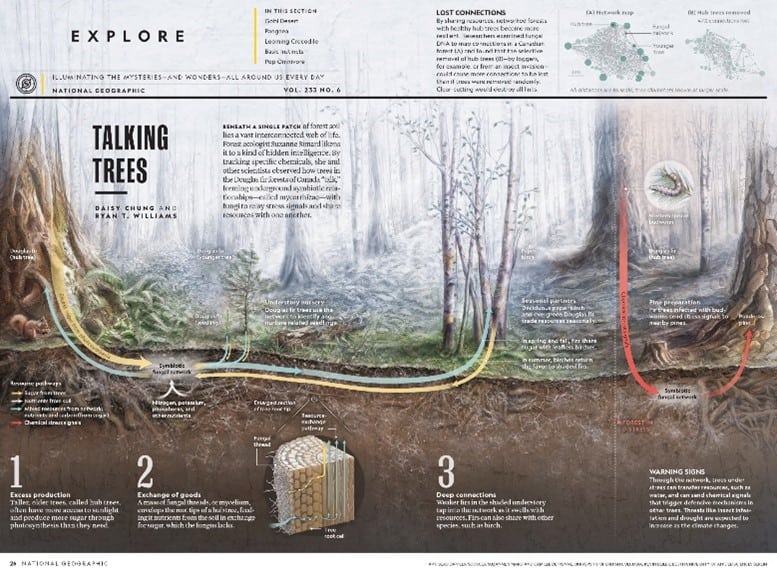

Understanding the relationship between humans and the rest of nature is important for the communication of rewilding to the public, because at the heart of this is the hope that people will find ways to occupy their place in the global ecosystem without exploiting that ecosystem to that point of damaging it. Suzanne Simard’s book, Finding the Mother Tree, is the story of her life’s work in forest ecology in North America, the narrative weaving together her family history of forestry and logging in British Colombia, with her own experiments in observing carbon sharing along fungal networks between trees, and her discovery of communication between different tree species along these mycorrhizae. Her book, and ongoing Mother Tree Project, explain the complexity and crucial importance of relationships between different species (see Figure 1), including the human species as an integral part of nature. The recognition of humanity as a part of such a constantly emerging web of exchanges could help us towards understanding and communicating rewilding. Rewilding is a positive strategy that acknowledges humans as actors in and parts of nature, and should not be dismissed as a negligent option, or as anti-human, because “For any rewilding strategy to succeed, society and nature need to be fully integrated.” (Carver et al., 2021). The images in figure 1 show two different approaches to visual explanation of ecosystem connectivity.

Figure 1, two images illustrating ways of showing the complexity of relationships between organisms in a forest environment, conceptual (Left, Beiler et al, 2010) and illustrative (Right, Chung and Williams, 2021). Both images reproduced by The Mother Tree Project, 2021.

In his influential manifesto for rewilding, ‘Feral’, George Monbiot reports the words of sheep farmer Dafydd Morris-Jones:

With blanket rewilding you lose your unwritten history, your sense of self and your sense of place…if you eradicate the evidence of our presence on the land…you write us out of the story…if you argue for wilderness for its own sake you’re still imposing a human point of view.

Monbiot, 2014: 177

The logic of this statement is difficult to counter, if we have a world view in which humans are outside of nature and believe that wilderness therefore must entirely exclude human actions. Some academic interpretations do perceive rewilding as an attempt to remove humanity from the landscape entirely, including an erasure of histories of occupation and land management (Jørgensen, 2015). Writing in this field often refers to ‘nature and people’ (for example Carver et al., 2021). Any sustained polarisation of humans and the wild, however, is problematic for advocates of rewilding, as it may, intentionally or not, communicate a sense that landscapes without any trace of human presence are the desired outcome. As people are so closely bound to place for not only their livelihoods and social bonds, but also their very identity as individuals (Beery, Ingemar Jönsson and Elmberg, 2015), attempts to exclude them from landscapes they have occupied is unethical and will prompt resistance. Therefore, whilst respecting local bonds to place, a different conception of people’s role in ‘their’ landscapes might be needed.

Place attachment, an innate tendency to form bonds with a place, particularly the one where a person spent their childhood (Beery, Ingemar Jönsson and Elmberg, 2015) has been an emerging field since the 1990s (Manzo and Devine-Wright, 2013). These bonds are important to rewilding projects because the significant change in land use that they implement requires a deep and sensitive understanding of local psychological and pragmatic attachments to landscapes. Carrus et al have examined the idea that pro-environmental behaviours, such as through volunteering or community activism, will arise from strong place attachments, hypothesising that people with such bonds would put benefits to their place before self-interest (Carrus et al., 2013). They found, however, that in places where there is strong place attachment, landscapes designated as protected can be perceived locally as a threat to the economy and seen as an imposition on a community. In these cases, perceptions of global benefits (such as from climate change mitigation) were overridden by perceived local disbenefits, such as changes of use for pro-environmental initiatives like wind turbines. If change through rewilding is to be accepted it may need to be demonstrated to be of local value, not only global, national or regional.

The concept of ‘nature connectedness’ explores attachment to a type of place, perceived as ‘natural’, rather than to a specific location. Natural England has conducted the Monitor of Engagement with the Natural Environment (MENE) survey since 2009. Data is collected across England to track the population’s connection with nature, including with regard to demographics, environmental attitudes and behaviours. Among the many findings (helpfully communicated through a Storymap) are that better access to and time spent ‘in nature’ has significant benefits to individuals in terms of health and happiness, but also to wider society and the economy (Natural England, 2019). One key conclusion of the study is that promoting access to nature should be an aim in itself, because of these benefits. In addition, they find that nature connectedness is a “significant factor in relation to wellbeing and pro-environmental behaviours “(Natural England, 2020: 5). This double benefit, to people and environment, is a strong basis from which to argue that promotion to the wider public of rewilding projects is therefore a desirable activity. It is important to recognise that the MENE findings do not necessarily imply that ‘green spaces’ must be created/maintained solely in order to service the needs of a human population. Taking the broader view, if we are not separate from landscape, or using nature simply as a resource, or framing ourselves as a species competing with others for an evolutionary ‘win’ (Midgley, 1995) then we can take our part as humble and cooperative community members in a wider ecosystem (Leopold, 1968; Simard, 2021; Monbiot, 2014). As a species, we have become accustomed to seeing ourselves as either entirely separate from nature, or at the very top of the tree, superior to and in charge of other species. Rewilding projects need to challenge this view both because it is contrary to the very essence of what rewilding is about, which is the interconnectedness of all species, and because it is damaging to a wider understanding of the meaning of such projects. This, then, is the second key theme identified through this research: humans as nature.

Literature Review Part Three: Illustrating Affordances

This study specifically explores the relationship of people with rewilding through visual media, rather than embodied experiences of rewilding projects. This recognises that photography, in particular, is increasingly powerful in constructing our perceptions of nature, with so many of us being more likely to view landscapes on a daily basis through social media rather than through our physical presence. It builds upon a body of research into preferences for images of landscapes as comprehensively reviewed and expanded by Kaplan and Kaplan in their influential book The Experience of Nature, a Psychological Perspective (1989). The Kaplans’ research provides a precedent for this type of study, but it took place before the advent of the internet and smart phones, before the establishment of the concept of ecological rewilding, and also prior to widespread popular concern about climate change and mass extinction. This study is therefore an attempt to begin to understand patterns of preference for photographs of rewilding landscapes in a changed global context.

The creation and viewing of images of landscape has arguably never been more culturally prevalent or accessible. Many of us constantly frame and re-frame the landscapes around us through digital photography. Contemporary artists still use and repurpose the conventions of landscape painting; modes of practice which tell a story about the history of our perceptions of nature (Harris, 2018). In this way, human connection with nature has been continually expressed through visual media over many centuries. Modern aesthetic appreciation of landscape in Western culture began to grow during the Renaissance and develop through the 18th century, with the development of three key aesthetic notions, according to Allen Carlson: “the beautiful, which readily applies to tamed and cultivated gardens and landscapes…the sublime… the more threatening and terrifying of nature’s manifestations, such as mountains and wilderness, [and] the picturesque.” (Carlson, 2020). These different strands of the visual celebration of nature may continue to offer some cues for understanding the response of people to images of wildness online. Many people appreciate constructed notions of ‘the beautiful’ through horticulture, possibly because it is an expression of human control over nature, as people create their own world to which they can retreat (Weilacher, 2015). It is a cultural practice that depends on human maintenance regimes, giving the person a central role in the garden, through which they understand their place in relation to the rest of nature, as designer and manager: the relationship enacted through procedures of constant regulation. An appreciation of wildness, however, does not necessarily require a human role in the viewed landscape. This might make images of wildness less engaging – because they do not always offer a place for us.

The concept of ‘thesublime’ may take us a step closer to understanding the potential for positive human responses to images of rewilding. Up until the Renaissance, in the Christian world, wild places had been seen as evidence of humanity’s fall from grace, cast out of the walled garden of Eden, exposure to wilderness being the punishment of humanity (Carlson, 1999). This made possible an intellectualised appreciation of wildness – the sublime – at a distance which created a sense of safety and degree of ‘knowability’ of that wild world. To enjoy the sublime is to accept the complexity and unpredictability of nature, and in the nineteenth century, was to celebrate feelings of awe and experience the terror of the potential ferocity of landscape, (Price, 1810; Midgley, 1995) including appreciation of such things as natural rugged rock faces and the transient beauties of weather phenomena (Macfarlane, 2003) as can be seen in Figure 2. By the late the nineteenth century the growing acceptance of theories of evolution perhaps meant that humanity’s future was perceived as increasingly separate from the wild, “leading man away from the rest of nature as fast as possible, as giving him the hope of escaping continuity with it after all” (Midgley, 1978: 197), whilst at the same time enjoying the sublime as an intellectual and emotional experience.

From the late 18th century, the picturesque ideal came to the fore, with its growth in popularity amongst wealthy English tourists who pursued picturesque experiences, for example in the ‘scenic’ destinations of Scotland and the north of England. Unlike the domestication of the wild inherent in the pleasures of a garden, the notion of the picturesque, “finds interest and delight in evidence of human presence” (Carlson, 2020) in notionally natural landscape settings. Designed landscapes were celebrated by artists, who in turn influenced landscape designers. This idealised mode for the viewing of landscapes has arguably never been replaced and has indeed boomed in its influence on the thinking of the Instagram generations. Instead of distancing the human viewer from the object of their gaze, an image in the picturesque tradition presents the viewer with a human relationship with nature, whether it be through depictions of people, human-made structures or artefacts, or through the taking of a ‘selfie’. The movement was so influential in the UK that Nan Fairbrother argued that the countryside “can fairly be considered as one of our national artistic achievements” (Fairbrother, 1970).

The Kaplans recognised the strong preference for the natural world in human nature but acknowledged that not everything that is natural is preferred. They found that “preference seems to be intimately related to effective functioning…that one should favour a path …that facilitates functioning, is hardly surprising.” (Kaplan and Kaplan, 1989: 68). They grew their understanding from the work of Gibson, who first developed his concept of affordances in 1979. Affordances are our perceived opportunities for action offered by any given environment. For example, a pathway through a woodland is quickly perceived by the person viewing it as offering the possibilities for use, as long as the individual has the physical ability to walk or ride. Due to human evolutionary preference, in outdoor environments there are many and diverse affordances, for example we will rapidly perceive places to hide from predators and available sources of food and water (Heft, 2010; Gibson, 1986). Individual needs or interests will also determine perception of affordances. Heft gives the urban example of a public square with low-level stone ledges which provides interesting affordances to a teenage skateboarder, but not to someone of impaired mobility. The affordance is created in the territory between the abilities and preferences of the individual and the observable qualities of the place.

In the context of a photo-based survey, subjects are not physically present in the landscapes they are viewing, so the individual is taking on ‘the spectator stance’ (Heft, 2010) in which they are detached from the physical realm of the landscape. Heft argues that viewing photographs is the ‘natural extension’ of viewing landscape paintings, an activity, he argues, which supports the dominance of the picturesque ideal in constructing our attitudes to landscape. Picturesque conventions tend to support carefully composed, immobile, framed and self-contained, images, and yet they may perhaps still be capable of suggesting wildness and process: a photograph could hint at something much more unruly and undesigned and could perhaps be used to depict an environment that is constantly in motion (Carlson, 1999).

The idea of affordance suggests the possibility that one strategy for engaging the passive viewer in images of landscape is to ensure that images include evidence of humans as part of the landscape, by signalling a range of potential affordances. These may perhaps be clearly signalled, such as including an image of a person on a path through a woodland, or could be more implicit, for example the presence of a fingerpost indicating a human presence in the landscape. As the physical reality of accessibility of landscape is important to many people, it is probably also important to readily communicate or signal that accessibility to the wider public. The concept of legibility of landscape is relevant here and relates to the idea of affordance. Legibility, thought to be a desirable property of a designed landscape, refers to a person’s sense that the landscape they are viewing would be straightforwardly navigable through such elements as landmarks and a degree of visual access (Herzog and Leverich, 2003). It is worth considering that improving the legibility of the landscape could engage an individual’s support for a rewilding project, even if they have no intention of physically visiting it. A significant proportion of an online audience may wish to engage with such projects for the most part as observers, rather than being physically present. This does not necessarily detract from their participation as members of a dynamic online community. Support might be expressed in a spectrum of ways from following social media accounts to donating to charities or signing pro-ecology petitions to parliament. It may even contribute to a person’s decision to vote for a political party, as suggested by the inclusion of rewilding in Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s 2021 keynote speech to the Conservative party conference in Manchester (Johnson, 2021).

The third key theme identified through this literature review is therefore the illustration of affordances in rewilding landscapes.

In summary of the literature review, the three following themes emerge as potentially being useful in targeting the public communication of rewilding;

- Open-ended Processes. Understanding the challenge of communicating and accepting complex and interrelated open-ended processes, rather than specific target outcomes. Ongoing processes are resistant to measurement and assessment, and furthermore there is scientific debate over what those processes should be.

- Humans as Nature. The idea of the wild seems to many of us to exclude or even threaten humans, when in fact humans can be conceived of as being very much part of nature, and this can be communicated through visual media. This could result in more pro-environmental behaviour as well as increased support for rewilding projects.

- Illustrating Affordances. A hypothesis that the inclusivity of people of all kinds within rewilding projects needs to be visually signalled by indicating that human presence is valued in these landscapes, and that there are opportunities to ‘be in’, and ‘do things in’, these places.

Interviews with Practitioners

I interviewed five practitioners in order to guide and inform my research, and to begin to tease out some of the common themes and challenges relevant to the communication of rewilding. Two of the interviewees are employees of large, national charities with remits broader than just rewilding, both based in Cumbria. The third is director of a targeted rewilding charity, the fourth is founder of a smaller campaigning organisation, and the fifth a specialist media consultant, who works for rewilding organisations. This cross-section of people from varying contexts within the field allowed me to gain a reasonably rounded picture of the concerns of experts who are fully personally invested in the success of rewilding projects. Each participant has given their consent to be named and is briefly introduced here. All interviews took place online, apart from Rachel Oakley, who very kindly spoke to me whilst walking around Ennerdale. Many thanks to all these interviewees, who were supportive, very informative, and generous with their time and in offering research leads.

Rachel Oakley (RO) is Partnerships Manager for the National Trust at Wild Ennerdale in Cumbria. Wild Ennerdale is a partnership of 20 years standing, between the Trust, United Utilities (who own the land), Natural England and Forestry England. Their shared vision is “to allow the evolution of Ennerdale as a wild valley for the benefit of people, relying more on natural processes to shape its landscape and ecology” (Wild Ennerdale, 2022). Although the word ‘rewilding’ does not appear with any prominence in any of their online materials, the project includes a ‘future natural approach’ to managing the forest, a planned beaver reintroduction to introduce dynamic aquatic disturbance and the use of three herds of Galloway cattle to disturb the seed bank in the ground and create a ‘patchwork’ of plant ecologies. Where the cattle have been grazing for more than 10 years there has been a 65% increase in bird species (Wild Ennerdale, 2022). The partnership encourages hiking, biking, canoeing, orienteering, horse riding and climbing at Ennerdale, producing resources to support some of these activities and signposting them on their website.

Lee Schofield (LS) is Senior Site Manager at RSPB Haweswater in Cumbria, and author of the recent book, ‘Wild Fell’, about his experiences in the job. Haweswater is the largest reservoir in the north of England and supplies drinking water to over 2 million people. The RSPB first became involved at the site when Golden Eagles bred here in 1969. They now pay United Utilities, who own the site, an agricultural rent, and manage the land with the primary aim of enhancing both water quality and biodiversity. One of the ways of achieving this aim has been to reduce the number of sheep by approximately 2/3, which creates a more resilient upland in two ways. The longer sward resulting from the reduced grazing retains moisture in periods of drought, but also helps to slow surface water flow and reduce flood risk. (Schofield et al., 2020). Schofield finds that the future economic reality may be that public funds can no longer support monocultural sheep farming in the UK uplands. The RSPB run a large hill farm at Haweswater, and in 2018 they published a financial report showing that they made a profit of £97per ewe and her lamb, but this is due to public subsidy; “without such subsidy the corresponding figure would have been a £135 loss” (Schofield et al., 2020: 257).

Pete Cairns (PC) is a photographer and Executive Director of Scotland the Big Picture, a campaigning organisation with the vision of “a vast network of rewilded land and water across Scotland, where wildlife flourishes and people thrive” (Scotland the Big Picture, 2022). They aim to re-establish natural processes, restore ecological webs, improve connectivity of wilder landscapes across Scotland and assist communities in building a nature-based economy that supports ecological recovery. Their work is diverse and their online presence an inspirational example of ‘positive storytelling’ about rewilding, including a wide range of very high-quality photographs and short films. They undertake specialist media work for other organisations, including Rewilding Britain and Rewilding Europe, and in 2021 worked with Wild Ennerdale to produce a short film about the project there.

Alan Cranston (AC) is a founding member and, at the time of interview was Chair of the small charity Hen Harrier Action, which looks to engage the public with its vision that “the UK’s uplands should be places where nature thrives undamaged and unharmed by human activity” (Hen Harrier Action, 2022). They campaign for thriving wildlife, better public policy to support upland ecologies, an end to raptor persecution, and they support human enjoyment of upland landscapes.

Richard Bunting (RB) is a media consultant specialising in work for ecology-based organisations such as Rewilding Britain and several other rewilding charities, including The Beaver Trust, Trees for Cities, Scotland the Big Picture, and the Scottish Rewilding Alliance. His work includes social media, websites and press. He is a former Amnesty International Director of Communications and currently edits the online magazines ‘Green Adventures’ and ‘Little Green Space’.

Findings Arising From Interviews

Through a process of notetaking and mind-mapping, the remarks of interviewees are grouped, below, according to emerging linked topics. The topics are inevitably interlinked and have overlaps. Initials indicate sources of individual comments. Each person was asked the same core questions (see appendix a), with additional different questions added according to the direction that the interview was taking.

a. Celebration of Nature

The traditional media are alert to rewilding stories and tend to focus on tension arising between farmers and ‘rewilders’ (RB). Photos are seen as a powerful tool in countering this with positive content (RB). Similarly, photos of top predators such as wolves can generate fear and dislike in the public through entrenching false narratives about rewilding (RB). Images of dead birds are best avoided (PC) and have a poor ‘reach’ on social media (AC). References to sheep are very sensitive (RB). It is preferred that inspirational stories be showcased (PC) and that images are used that reflect the aspirations of the project for the future, rather than using images of areas that are only very slowly recovering, for example, as these may give the impression of lack of success (RO). Use of images of very nature-depleted landscapes such as grouse-shooting uplands was thought to be unhelpful (RB and AC) as their depleted nature may not be apparent to all (see ‘perceptions of beauty’, below). A key challenge here is to illustrate optimistic aspirations for the future without being disrespectful of the past history of the landscape (RO), and also to disrupt complacency without encouraging pessimism and inaction due to negativity (RB). Overall, positive messaging and a ‘less shouty stance’ were seen as very important (AC).

b. Open-ended Processes

All interviewees highlighted the importance of illustrating ecological processes and discussed the challenge of unknown outcomes; for example “We don’t have an endpoint” (RO). There is, however, still a need to achieve visible results to indicate that measures being taken are benefiting the landscape (RO) and also to deliver value to local people (LS). It was considered important to recognise that non-intervention is not neglect, it is in itself a management tool (RO). The dynamism and adaptability of a rewilded landscape were mentioned as themes through which to emphasise the positivity of change and process, with the complexity of these topics acknowledged (LS). As an example of this, the case of Storm Desmond in 2015 was cited; 5,200 homes in Lancashire and Cumbria were flooded, but there was no damage at Ennerdale, due to the river being well-connected to its catchment (RO). Natural resurgence and spontaneous regeneration of trees was considered a useful thing to celebrate (LS) as it offers hope and perhaps a sense of empowerment in the face of the seemingly overwhelming climate crisis (RB). It was felt that there was not enough honest debate over why nature recovery has become necessary, and the land management practices that have caused species loss (RO) but all interviewees mentioned the sensitivity of this, because rewilding projects cannot realistically thrive without farmers as willing partners. It was acknowledged that rewilding projects need to deal with the long occupation of the place by people, for example at Ennerdale where there are many archaeological remains, including four medieval longhouses (RO). Communicating a holistic approach is a challenge (RO) because of the sheer scale and complexity of the interrelated processes involved but learning about rewilding is an opportunity to learn and change (RO).

c. Perceptions of Beauty

Interviewees noted that aesthetic preferences are highly subjective, with some people enjoying viewing severely nature-depleted landscapes (AC), perhaps because the shifting baseline has led them to think that the current condition of the countryside is its appropriate state. It is important to combat this loss of environmental general-knowledge (RB) and ‘ecological blindness’, through which we are conditioned to accept the familiar as the natural (PC). Sometimes local people felt they had to ‘defend’ not only the culture or economy, but the beauty of a place from rewilding proposals (RO). Because so few places are as richly diverse as they could be we lack well-known examples of richly diverse nature, so animated films are a way of demonstrating potential improvements, and these might help combat shifting baseline syndrome (AC). It is important for people to understand the diversity of landscape typologies and species that could be considered beautiful (RB). In the UK we have a problem with prioritising the tidiness of outdoor spaces, and a reluctance to accept the messiness of a natural ecosystem (RB), and it may be best to avoid using images that are ‘too messy’, for example depicting bare mud or footpath erosion (LS). There was a feeling that images of ‘nice’ animals were generally very successful in reaching a wide public (AC). Two interviewees said that national parks are ‘sold’ to visitors with a narrative about beauty, without questioning how adaptable and resilient to climate change they are (RO and AC).

d. Broadening Appeal

The emotional impact of images on a general audience was considered important, recognising that relationships with nature, and with images online, is likely to be more emotional than it is rational (PC). It was considered important that media content produced by rewilding organisations does not just reach out to ‘people like us’ (meaning those already involved in rewilding)(AC) but achieves a broader appeal which reaches across different demographic groups and resists any tendency towards ‘silos and tribes’ (PC). Public engagement was seen to be a core activity by some interviewees (AC and RB). Media misrepresentation about people-less landscapes as a direct result of rewilding programmes was thought to have been a public relations problem in specific cases (RB), and so the positioning of people within nature was seen as very important (RB). When asked specifically about their target audiences, the interviewees acknowledged that farmers, land managers and landowners were key groups, because these are the people who have the most power to implement rewilding projects. If you can show that something is embedded at a local level, that can cascade the change (RO). It was also noted that people who use the countryside for recreation do not necessarily engage with complex ecological issues in those landscapes (AC and RO). Illustrating the connectivity between habitat and people was identified as important (PC). There was some feeling that conservationists have not fully grasped that rewilding has to be, in part, a marketing exercise (PC). For one participant, government agencies were the most important recipients of advocacy of rewilding (LS) in order to improve public policy. Lack of diversity of people interested in rewilding was acknowledged as an issue to be addressed, with projects attracting mainly “older, white, middle class” people (LS), and a “middle aged middle class middle England audience” (PC) which needs to be broadened. One participant clearly stated that the most important thing “is to keep emphasising the role of people in landscapes into the future… and to do more work on the communication of that” (LS). At Ennerdale, photos of and messages of thanks from a woman accessing the land on her mobility scooter had caused great delight (RO).

e. Storytelling

Some ‘good news’ stories were mentioned as being hard to sell to the public, for example the internationally important recruiting population of freshwater mussels at Ennerdale (RO) which, understandably, may not capture public attention in the same way as a photo of a field of flowers or a playful red squirrel. Illustrating ambition in aspirations for the future was felt to be important, communicating the possibility that people could reverse the collapse in biodiversity through positive ‘problem-solution-action’ approaches (RB). Illustrating context for images is challenging and very important, to avoid misinterpretation (RB). Creating a ‘sense of the wild’ is important, as true wildness is an abstract concept (RO) and doesn’t really exist anywhere in the UK. One interviewee particularly felt that images of people busy doing things in the landscape were very useful, for example volunteers doing work on site and visitors enjoying a place, to avoid the perception of a landscape without people (LS) and implies that there are different roles and activities available for people. One participant particularly sought to avoid using the word rewilding as it alienates local people, by suggesting that what came before is not good enough, and so ‘putting peoples hackles up’ (LS). It is felt to be a tarnished term due to well established false narratives (LS). The notion of psychological ‘stepping stones to wildness’, such as semi-wild herds of cattle, was suggested as part of a transition to different thinking (RO). A point was strongly made about the value of optimising impact by carefully selecting images for specific purposes and telling compelling stories with identifiable characters or themes, such as in the Riverwoods animation made by Scotland the Big Picture, in which the story is ostensibly about salmon but it actually forms a narrative about the whole river catchment and its ecological processes (PC).

Commentary: Themes Arising From Interview Topics

The interviews indicate some support for themes 1 to 3 as identified through the literature review;

Theme 1, ‘open-ended processes’, because of the need to locate media messages clearly in a context of the ongoing, complex and uncertain nature of the progress of rewilding, in order to avoid misrepresentation.

Theme 2, ‘humans as nature’, because of the acknowledgement that people and human culture need to be depicted as having a place in rewilding landscapes as functioning parts of the ecology.

Theme 3, ‘Illustrating affordances’, because this is a way of broadening appeal by indicating to people that there are diverse ways to be present in rewilding landscapes, which have many things to offer in terms of human activity.

In addition, a further two themes can be identified;

Theme 4, ‘celebration of nature’, due to the importance of focusing on positive potential outcomes for landscapes in the face of species loss and widespread environmental degradation. It is recognised that images perceived as being worth celebrating will be different for different people.

And finally, drawing on the interview topics of ‘perceptions of beauty’ and ‘storytelling’-

Theme 5, ‘resetting the baseline’, because an essential part of the storytelling of rewilding needs to be that richer, more diverse ‘past’ ecologies can be restored. The value of animations in achieving this.

Also emerging from the interviews is a sense of some of the most difficult challenges facing these communicators of rewilding. These are summarised as follows;

Split audiences. At the same time as appealing to a national audience, rewilding projects also have to speak to their local audience, in particular neighbouring farmers and landowners/land managers. This is difficult because the content, tone and nature of engagement materials, as well as the likely degree of engagement, will be very different across the two audiences, for whom very different things are at stake.

An education paradox. Education is a sensitive word in the context of any public engagement with landscape because it can prompt concern that ‘outside’ experts might come into a local area and attempt to impart their knowledge to local inhabitants, thereby assuming a deficit in understanding in the local person, with all their unique knowledge of the place, and a superiority on the part of the ‘educated expert’ (see for example (Arnstein, 1969). This dynamic is to be avoided at all costs, however, given the problem of the shifting baseline, paired with the truly complex ecological science involved, how will people become accepting of rewilding without knowledge of its principles and strategies, and seeing how these are being applied in that place? For rewilding projects, fruitful online presence goes far beyond ‘clickbait ‘, as complex projects need to be communicated accurately, with their aims and ethos also connected securely to human concerns.

Valuing culture yet moving on. There is a very significant difficulty inherent in looking to provoke revolutionary changes whilst at the same time genuinely respecting past cultural relationships with landscape. Telling people that their lifelong practices have critically damaged the environment they love and belong to will always be controversial and takes a long time to have an effect, as can be seen with many other chronic environmental issues, such as our dependence on carbon-based fuels, or over-consumption of manufactured goods.

The Survey

In order to test out some of the ideas drawn from the literature review and interviews, I designed and carried out an online survey of preferences for photographs, which was live between 31st January 2022 and 28th February 2022. 385 people responded. The survey was intended primarily to explore themes 2 and 3, through the hypothesis that participants will prefer images that signal affordances over those that don’t. There is not enough capacity, through a small, independent, one-off survey, to explore all five of the identified themes. Themes 1 and 5, in particular, resist testing through a ‘snapshot’ approach due to the need for contextualisation, ideally within a specific rewilding project. Some of the photos used are arguably more clearly celebratory of nature than others (theme 4), so some reflection on this theme is also possible.

Method

The survey was based broadly on an approach tried and tested by Kaplan and Kaplan. I asked people to rate their preferences for photographs of landscapes on a five-point Likert scale. This method was chosen because using photographs offers a triangulation opportunity (Stedman et al., 2013) through which voices of the public could be heard. Kaplan and Kaplan selected the most and least preferred scenes as being the more interesting for examination (Kaplan and Kaplan, 1989), and this approached has been used to extract and report on my data. In order to analyse responses, I added up the total scores for each photo by weighting the responses. Each ‘like very much’ response. For example, was given 5 points, ‘like’ was given four points and so on down to 1 point for ‘dislike very much’.

I selected photographs on the basis of several criteria in order to try to control for extraneous factors influencing preferences. All the images of landscapes were taken from online sources associated with UK rewilding projects, and all of them depicted those projects, apart from photograph 24, which was kindly supplied by Black Girls Hike UK. This was necessary because it had not been possible to find an image clearly featuring a woman of colour in the online presence of any of the rewilding projects, and it was important to represent human diversity in the survey. There were also four photos of animals which were sourced from UK rewilding websites but were not necessarily taken in the UK. All photos of landscapes showed scenes of clement weather, with vegetation in partial or full leaf. No winter or autumn images were used, and nor were there any close-ups. Given the subjectivity of people’s opinions it was not possible to entirely control for the perceived quality or artistic merit of the photographs. An effort was made to use images of similarly good quality, and to avoid any that might stand out as very high-quality professional photographs.

The key variable determining photo selection was the degree of affordance illustrated. I chose four landscape photos for each of five categories, see Table 1. Photos were sequenced in a random order throughout the survey.

| Category number, indicating degree of affordance | Images included in this category |

|---|---|

| 0 | No affordances signalled, for example photos of impenetrable woodland, a meadow without path or any sign of human presence, an image of a river without any means for people to cross or access the water. |

| 1 | Some implied or ‘natural’ affordances are signalled, such as a river with a shore where a person might walk or paddle, a forest with an open floor that could be walked, or a lake with accessible shoreline for boating or swimming. |

| 2 | Photos include human-made artefacts that show both evidence of human presence and things to do in the landscape, such as a visitor car park, interpretation boards, a camping field and clearly designated footpaths. |

| 3 | All pictures include people, but they are inactive, for example standing or sitting looking at a view, or posing for the camera. |

| 4 | This category of pictures signals the highest degree of affordance, illustrating people hiking and doing voluntary maintenance tasks. |

An ‘animals’ category was added in order to give some indication of whether people preferred images of domestic animals (ponies at Haweswater) semi-domesticated livestock (cattle at Ennerdale) an attractive but ‘safe’ native mammal – a red squirrel, or a fully wild top predator – a wolf in a birch woodland.

Participants were also asked to state whether they considered themselves to have lived mainly in cities or in the countryside, or neither of these. This enabled me to check whether city people and country people had widely diverging views or not.

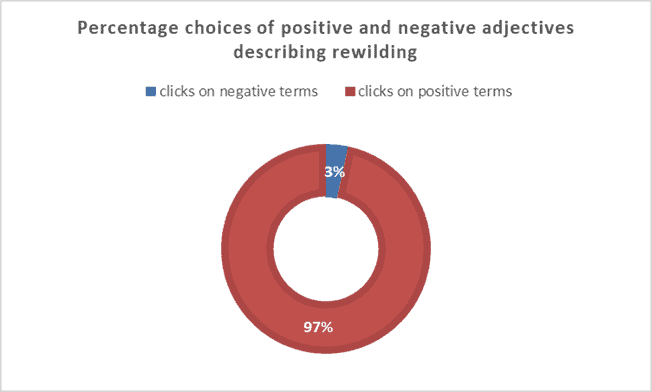

All participants were asked a final, text-based question to gauge their attitude towards rewilding, see Figure 3. They had the option to choose any number of adjectives from a list of 12, of which six words indicated a pro-rewilding stance, and the other six a negative opinion of rewilding. This meant that I could gauge whether the group of participants was predisposed to like photos of wilder places. This was important because they were a self-selected group who had accessed the survey via shared links on social media, so I was unable to control who responded to the survey.

Survey Results and Commentary

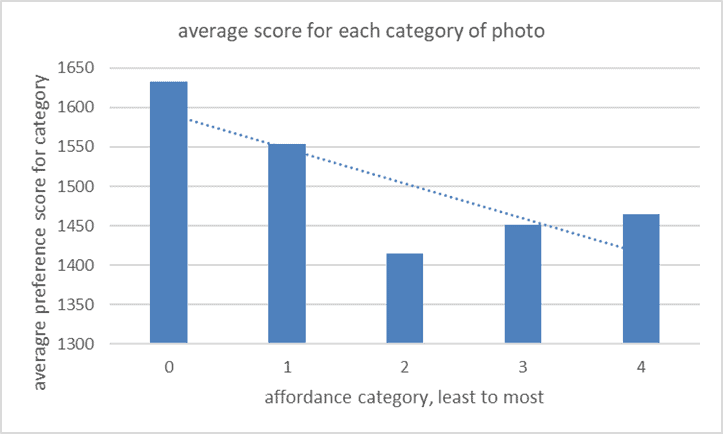

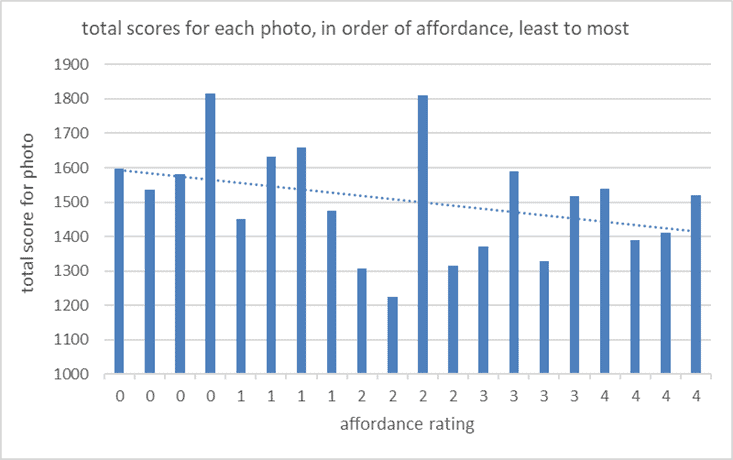

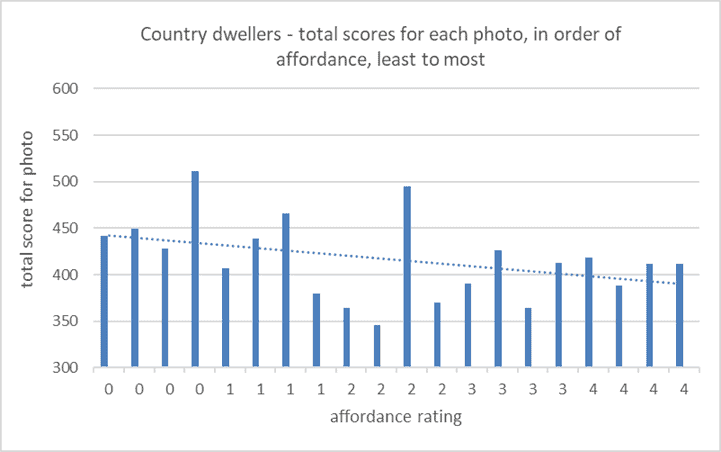

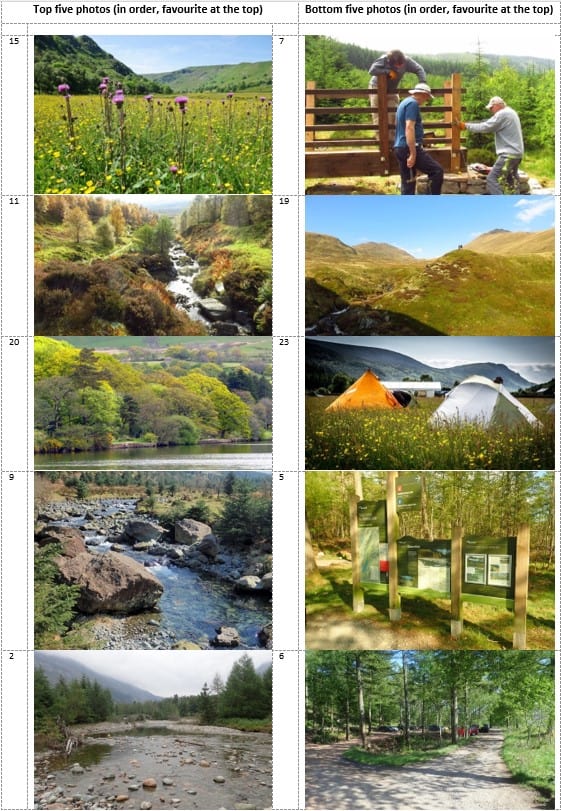

My hypothesis that participants will prefer images that signal affordances over those that don’t, proved to be incorrect. The reverse was true, as can be seen from the trend line Figure 4, which shows the average score for each category of photo, zero being the ‘no affordances’ category, and 4 being the category showing people doing things in the landscape: people preferred images showing no obvious evidence of human presence over those with people in them. Figure 5, below, is a graph showing preference scores for each individual photo in each category, and this indicates some notable outliers to the trend. These are firstly the two top-rated photographs, numbers 11 and 15, which were the image of a path next to a stream at Ennerdale and the wildflower meadow, respectively (see Error! Reference source not found.). Secondly, the two least preferred photos, numbers 5 and 6, the Ennerdale interpretation signage and the car park, respectively (see photos in Error! Reference source not found.). The downwards trend is still apparent if the answers of city dwellers are separated out from the answers of rural dwellers, see Figure 6 and Figure 7.

It is possible that the reason for this reversal of the predicted pattern is the self-selecting nature of the participants. Arguably, only those with a pre-existing interest in rewilding would have clicked on the survey link when it appeared on their social media channels. In addition, the information gained through the text-based final question (Figure 3) indicates that the survey reached an audience that was already strongly in favour of rewilding. Figure 8 shows that a very small proportion of negative descriptors of rewilding were selected by participants. It may be, therefore, that these people most enjoyed the pictures that showed the greatest degree of wildness, precisely because they showed the least conspicuous, or zero, human presence.

That only 3% of the choices of adjectives across all participants were negative descriptors might indicate that this group of people did not represent a typical sample of members of the public, although it is possible that it is a reflection of a very high level of support for rewilding in the UK, as a YouGov poll for Rewilding Britain in 2022 found that in a representative sample, only 5% of British adults were against rewilding and 81% were in support (Rewilding Britain, 2022).

Analysis of the small sample of people who ticked negative descriptors shows that, for the 17 people who chose to describe rewilding as ‘irresponsible’, there is also a decreasing trend in preference with increased affordances (see Figure 9), however the small sample size here may mean that no conclusions can be drawn from this. The favourite photo for this group was, in common with the group as a whole, photo 15 the wildflower meadow, and the least favourite, again, was photo 6, the car park.

Of the four photos with animals in them (Figure 10), the order of preference across all 385 participants, from most to least preferred, was red squirrel, wolf, semi-wild cattle at Ennerdale and ponies at Haweswater (which are shown laden with saddles and equipment). This indicates that the most clearly ‘domesticated’ animals were the least favoured, again suggesting a preference for wildness. If animal photos are included in the rankings alongside the landscape photos, the squirrel and wolf appear in the top five most liked pictures. This would perhaps support the idea that, amongst this sample, photos which are a celebration of nature are likely to be more popular (as compared to the car park and sign boards, for example). It would also suggest that continuing to use photos of top predators may help rewilding organisations to continue to appeal to their core online audience of people who support rewilding. However, the wolf was the least liked of the animal photos amongst the 17 people who used the ‘irresponsible’ descriptor, so wolf pictures may not help to reach out to new or cautious audiences.

Figure 10, the animal photos, least preferred on the left, most preferred on the right

The five most liked and five least liked landscape photos for the whole participant group (see Figure 11), suggest a number of interesting points. The favourite of all the photos is the only one of the 24 pictures that clearly features flowers. Four of the top five photos feature bodies of water. Human attachment to landscapes with visible water has been noted in previous studies and is sometimes cited as evidence of evolutionary landscape preferences (Adevi and Grahn, 2012; Kaplan and Kaplan, 1989). The top five photos feature either minimal affordances, or none. There are no people visible and the only evidence of any human presence in these photos is the narrow streamside path glimpsed in photo 11. There is a suggestion of a possible location to land a boat in photo 20, and a small shallow area of pebbles in photo 9, where it might be pleasant to paddle. Photos 15 and 9 have no obvious evidence of affordance at all. Apart from the wildflower photo, the top favourites feature trees as either the dominant or significant secondary feature in the composition. The five least-favoured photos all clearly show people or evidence of human activity. The least preferred is identifiable as being a car park, despite being dominated by mature trees. The third least popular, photo 23, has much in common with the top favourite, photo 15, but for the inclusion of the tents, perhaps suggesting that it is the tents that cause people not to favour the picture. In other words, human presence has possibly caused a big reduction in preference score for the photo.

It is important to recognise that using photographs of real places to measure people’s responses makes it difficult to control for all variables. As this is a pilot study it can claim to do no more than indicate a way forward to test the hypothesis on a wider range of participants and varying the nature of the photographs used. This is an inevitable aspect of seeking individual opinion about complex images (Kaplan and Kaplan, 1989).

Reflections on Survey Results

Before the advent of social media and associated technologies, Kaplan and Kaplan found that people will express an instinctive preference for safety in an environment, asserting that it is essential that people “not only perceive what is safe but also prefer it.”(Kaplan and Kaplan, 1989: 41). In 2022, however, we have many opportunities to look at images of nature and semi-natural landscapes, which can keep alive our interest in and attachment to these landscapes on a daily basis even though many of us inhabit urban places for almost all of our lives. Because these images offer no immediate or present threat to our safety, and whilst we in the UK are so infrequently in danger from immediate environmental threats, we have perhaps become more enthusiastic about accessing wildness through whatever channels we can. We also live in a time of growing concern about the chronic environmental threats of climate change, pollution and species loss. This may make us more disposed to appreciate evidence of the continuing existence of wilder places, when we are seldom in such landscapes in our day to day lives (Jepson and Bythe, 2020). In the 1990s Carlson emphasised the importance of cognitive understanding of the nature that we see, in order to appreciate “what it in fact is; and yet at the same time … appreciating nature as what it is for us.”(Carlson, 1999: 9). Lack of understanding of rewilding is a key challenge, especially in combating fear due to misinformation and misinterpretation in audiences local to a rewilding project (Carver et al., 2021), but human society is now perhaps beginning to realise that what nature “is for us” could determine the future for our own species, as we learn more about how we depend on other species continuing to exist.

Conclusions

The three research methods have drawn out five themes for potential use in visual communication of rewilding projects. More research on these themes is justified, using a wider range of images, including animations, and targeted sampling in order to reach a group of participants that is more representative of the UK population. The recommendations of this report, based around these themes, are as follows;

Theme 1 – open-ended processes should be communicated to both local and national audiences in a way that demystifies the science of rewilding. This knowledge needs to be offered in an accessible way, and animations are a good way to achieve this. A good example is ‘What does Rewilding Look Like?’, a video by Rewilding Britain.

Theme 2 – humans as nature should be communicated to local audiences as a priority because of the pressing need to emphasis the continuing role of people in their immediate landscape. The imagination of the national audience may also be captured by this theme, see exemplar animation by the Scottish Rewilding Alliance, here.

Theme 3 – illustrating affordances needs to be used carefully in order to signal to local people that they still have use of a particular landscape in a range of ways, but without alienating pro-rewilding audiences who may prefer images that evoke less populated places. The Wild Ennerdale ‘Activities’ web page is an excellent example of an organisation openly offering a wide range of activities to visitors who might be local or tourists.

Theme 4 – celebration of nature is probably of universal appeal, and is often achieved through photos of animals, although wildflower photos could perhaps be used more widely. Selection of the species for illustration should take account of the target audiences’ possible preferences for images connoting either safety, or conversely, for wildness. One example that illustrates semi-domesticated animals in way that may appeal to both audiences is the Tamworth Pigs gallery, on the Knepp Wildland website.

Theme 5 – resetting the baseline also needs to be communicated with some urgency to local and national audiences. An impactful example is Riverwoods, an Untold Story by Scotland the Big Picture.

Bibliography

Adevi, A. A. and Grahn, P. (2012) ‘Preferences for Landscapes: A Matter of Cultural Determinants or Innate Reflexes that Point to Our Evolutionary Background?’, Landscape Research, 37(1), pp. 27-49.

Amos, I. (2021) Call for Scotland to become world’s first Rewilding Nation. https://www.scotsman.com/news/environment/call-scotland-become-worlds-first-rewilding-nation-3137107: The Scotsman (Accessed: 28.4.22 2021).

Arnstein, S. (1969) ‘A Ladder of Citizen Participation’, Journal of the American Planning Association, 35(4), pp. 216-224.

Beery, T., Ingemar Jönsson, K. and Elmberg, J. (2015) ‘From Environmental Connectedness to Sustainable Futures:

Topophilia and Human Affiliation with Nature’, Sustainability, 7, pp. 8837-8854.

Beiler, K. J., Durall, D. M., Simard, S. W., Maxwell, S. A. and Kretzer, A. M. (2010) ‘Architecture of the wood-wide web’, New Phytologist, 185(2), pp. 543-553.

Carlson, A. (1999) Aesthetics and the Environment: The Appreciation of Nature, Art and Architecture (1st ed.). London: Routledge.

Carlson, A. 2020. Environmental Aesthetics. In: Zalta, E.N. (ed.) The Stanford Encyclopedia of

Philosophy. Winter 2020 Edition ed. <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2020/entries/environmental-aesthetics/>.

Carrus, G., Scopelliti, M., Fornara, F., Bonnes, M. and Bonaiuto, M. (2013) ‘Place Attachment, Community Identification, and Pro-Environmental Engagement’, in Manzo, L. and Devine-Wright, P. (eds.) Place Attachment: Advances in Theory, Methods and Applications (1st ed.): Routledge.

Carver, S., Convery, I., Hawkins, S., Buyers, R., Eagle, A. and Kun, Z. (2021) ‘Guiding principles for Rewilding’, Conservationn Biology, 35(6), pp. 1882-1893.

Case, P. (2018) Farmers must weigh up rewilding risk and reward: Farmer’s Weekly. Available at: https://www.fwi.co.uk/livestock/farmers-must-weigh-up-rewilding-risk-and-reward (Accessed: 15.3.22 2022).

Chung, D. and Williams, R. T. (2021) ‘Talking Trees’, National Geographic, (no. 6).

Corlett, R. T. (2016) ‘The Role of Rewilding in Landscape Design for Conservation’, Current Landscape Ecology Reports, 1(3), pp. 127-133.

DEFRA, Department for Environment, F.a.R.A. (2021) Rural Proofing in England 2020, Delivering policy in a rural context. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/rural-proofing-in-england-2020: UK Government.

Enck, J. W. and Bath, A. J. (2012) ‘Human Dimensions of Scarce Wildlife Management’, in Decker, D.J., Riley, S.J. and Siemer, W.F. (eds.) Human Dimensions of Wildlife Management. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, pp. 189-203.

Fairbrother, N. (1970) New lives, new landscapes. London: Architectural P., p. viii, 397 pages illustrations, facsimiles, maps, plans 26 cm.

Firth, L. B., Airoldi, L., Bulleri, F., Challinor, S., Chee, S.-Y., Evans, A. J., Hanley, M. E., Knights, A. M., O’Shaughnessy, K., Thompson, R. C. and Hawkins, S. J. (2020) ‘Greening of grey infrastructure should not be used as a Trojan horse to facilitate coastal development’, Journal of Applied Ecology, 57(9), pp. 1762-1768.

Gibson, J. J. (1986) The ecological approach to visual perception. Resources for ecological psychology Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers, p. xiv, 332 pages : illustrations ; 24 cm.

Harris, A. (2018) ‘Landscape Now’, British Art Studies, (10).

Hayhow, D., Eaton MA, Stanbury AJ, Burns F, Kirby WB, Bailey N, Beckmann B, Bedford J, Boersch-Supan PH, Coomber F, Dennis EB, Dolman SJ, Dunn E, Hall J, Harrower C, Hatfield JH, Hawley J, Haysom K, Hughes J, Johns DG, Mathews F, McQuatters-Gollop A, Noble DG, CL, O., Pearce-Higgins JW, Pescott OL, GD, P. and N, S. (2019) State of Nature 2019, https://nbn.org.uk/stateofnature2019/reports/: The State of Nature Partnership (Accessed: 15.3.22).

Heft, H. (2010) ‘Affordances and the perception of landscape.’, in Ward Thompson, C., Aspinall, P. and Bell, S. (eds.) Innovative approaches to research landscape and health: Open space: People space, 2. UK: Routledge, pp. 9-32.

Hen Harrier Action (2022) Our Vision. https://henharrierday.uk/ (Accessed: 20.04.22 2022).

Herzog, T. R. and Leverich, O. L. (2003) ‘Searching for Legibility’, Environment and Behavior, 35(4), pp. 459-477.

IPBES (2019) Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the

Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem

Services, Bonn, Germany: IPBES secretariat. Available at: https://ipbes.net/global-assessment.

Jepson, P. and Bythe, C. (2020) Rewilding, the Radical New Science of Ecological Recovery. Hot Science London: Icon Books.

Johnson, B. 2021. transcript of Conservative Party conference speech. https://www.conservatives.com/news/prime-minister-boris-johnson-speech-conference-2021: The Conservative Party.

Jørgensen, D. (2015) ‘Rethinking rewilding’, Geoforum, 65, pp. 482-488.

Kaplan, R. and Kaplan, S. (1989) The experience of nature : a psychological perspective. Cambridge ;: Cambridge University Press, p. xii, 340 pages : illustrations ; 27 cm.

Kohlstedt, K. (2016) Renderings vs. reality: the improbable rise of tree-covered skyscrapers: 99% Invisible. Available at: https://99percentinvisible.org/article/renderings-vs-reality-rise-tree-covered-skyscrapers/?utm_medium=website&utm_source=archdaily.com (Accessed: 18.3.22 2022).

Law, A., Gaywood, M. J., Jones, K. C., Ramsay, P. and Willby, N. J. (2017) ‘Using ecosystem engineers as tools in habitat restoration and rewilding: beaver and wetlands’, Science of The Total Environment, 605-606, pp. 1021-1030.

Leopold, A. (1968) A Sand County almanac : and Sketches here & there. Oxford University paperback ; GB263 N.Y.: Oxford University Press, p. 226 pages, illustrations.

Levitt, T. (2021) ‘It’ll take away our livelihoods’: Welsh farmers on rewilding and carbon markets: The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/dec/28/agriculture-recycling-carbon-farmers-reframe-rewilding-debate (Accessed: 15.03.22 2022).

Macfarlane, R. (2003) Mountains of the mind. First American edition. edn. New York: Pantheon Books.

Malloy, C. (2021) Cities’ Answer to Sprawl? Go Wild.: Bloomberg CityLab. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2021-10-22/urban-rewilding-aids-biodiversity-climate-resilience (Accessed: 18.03.22 2022).

Manzo, L. and Devine-Wright, P. (2013) Place Attachment: Advances in Theory, Methods and Applications (1st ed.). Routledge.

Midgley, M. (1978) Beast & Man : the Roots of Human Nature Florence: Routledge. Available at: https://public.ebookcentral.proquest.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=3060250.

Midgley, M. (1995) Beast & Man : the Roots of Human Nature, introduction to the revised edition Florence: Routledge. Available at: https://public.ebookcentral.proquest.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=3060250.

Monbiot, G. (2014) Feral : rewilding the land, the sea, and human life. London: Penguin Books.

National Geographic Kids (2022) ‘Return of the Missing Lynx’, (no. 199).

Natural England (2019) People’s Engagement with Nature a storymap celebrating 10 years of MENE. www.gov.co.uk: Natural England. Available at: https://defra.maps.arcgis.com/apps/Cascade/index.html?appid=d5fe6191e3fe400189a3756ab3a4057c (Accessed: 28.03.22 2022).

Natural England (2020) A summary report on nature connectedness among adults and children in England –

Analyses of relationships with wellbeing and pro-environmental behaviours., https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/monitor-of-engagement-with-the-natural-environment-survey-purpose-and-results: UK Government.

O’Rourke, E. (2014) ‘The reintroduction of the white-tailed sea eagle to Ireland: People and wildlife’, Land Use Policy, 38, pp. 129-137.

Pauly, D. (1995) ‘Anecdotes and the shifting baseline syndrome of fisheries’, Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 10(10), pp. 430-430.

Pettorelli , N., Barlow , J., Stephens , P. A., Durant , S. M., Connor , B., Schulte to Bühne , H., Sandom , C. J., Wentworth , J. and du Toit, J. T. (2018) ‘Making Rewilding Fit Policy’, Journal of Applied Ecology, 55, pp. 1114–1125.

Price, U. (1810) Essays on the picturesque.

Reading Borough Council (2021) Rewilding Reading. Available at: https://www.reading.gov.uk/leisure/outdoors/rewilding-reading/ (Accessed: 18.03.22 2022).

Rewilding Britain (2022) Four in five Britons support rewilding, poll finds. https://www.rewildingbritain.org.uk/news-and-views/press-releases-and-media-statements/four-in-five-britons-support-rewilding-poll-finds: YouGov (Accessed: 25.04.22 2022).

Schofield, L. (2022) Wild Fell. Great Britain: Doubleday.

Schofield, L., Teasdale, D., Hampson, D. and Ausden, M. (2020) ‘Balancing Culture and Nature in the Lake District’, British Wildlife, (no. April).

Scotland the Big Picture (2022) Our Take on Rewilding. Available at: https://www.scotlandbigpicture.com/our-take-on-rewilding (Accessed: 17.3.22 2022).

Simard, S. (2021) Finding the mother tree : discovering the wisdom of the forest. First edition. edn. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Stedman, R. C., Amsden, B. L., Beckley, T. M. and Tidball, K. G. (2013) ‘Photo-based methods for

understanding place meanings as foundations of attachment’, in Manzo, L. and Devine-Wright, P. (eds.) Place Attachment: Advances in Theory, Methods and Applications (1st ed.): Routledge.

Sturgeon, A. (2021) ‘Rewilding our cities: beauty, biodiversity and the biophilic cities movement’, The Guardian, 4.4.21.

Taylor, B. (2012) ‘Wilderness, Spirituality and Biodiversity in North America – tracing an environmental history from occidental roots to Earth Day’, in Feldt, L. (ed.) Wilderness in Mythology and Religion : Approaching Religious Spatialities, Cosmologies, and Ideas of Wild Nature Religion and Society ; v. 55. Boston: De Gruyter.

The Mother Tree Project (2021) About Mother Trees in the forest. https://mothertreeproject.org/about-mother-trees-in-the-forest/ (Accessed: 28.4.22).

Tree, I. (2019) Wilding : The Return of Nature to a British Farm. UK: Pan Macmillan.

Vera, F. (2009) ‘The Shifting Baseline Syndrome in Restoration Ecology’, in Hall, M. (ed.) Restoration and History: The Search for a Usable Environmental Past (1st ed.): Routledge, pp. 13.

Weilacher, U. (2015) ‘Is landscape gardening?’, in Doherty, G. and Waldheim, C. (eds.) Is landscape? Essays on the identity of landscape: Vol. Book, Whole: Routledge.

Wild Ennerdale (2022) Wildlife. https://www.wildennerdale.co.uk/wildlife/ (Accessed: 20.04.22 2022).

Wilson, C. J. (2004) ‘Could we live with reintroduced large carnivores in the UK?’, Mammal Review, 34, pp. 211-232.

Yeo, S. (2021) How is your local council managing its roadside verges?: Inkcap Journal. Available at: https://www.inkcapjournal.co.uk/how-is-your-local-council-managing-its-roadside-verges/ (Accessed: 18.3.22 2022).

Appendix A: Core Interview Questions

- What do you look for in a photograph or film to be used for publicity purposes?

- What would you avoid in such a photo?

- Are there any themes arising out of these images?

- Who is your audience?

- Do you have an idea of the demographics of the people engaging with your organisation?

- Do people have different ideas of what wild and rewild mean? Does it matter?

- What are the main challenges of your engagement work?

- What would be useful to you in terms of any output or findings from my research?

- How do you engage the unengaged?